Anti-Racism and Museum Ethics at San Francisco's Asian Art Museum

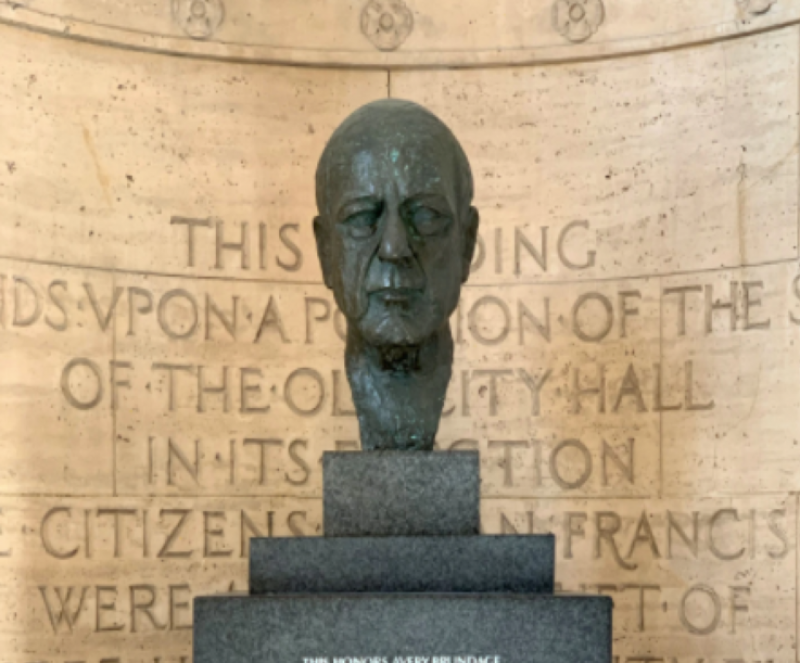

The bust of patron Avery Brundage in the foyer of the Asian Art Museum. Image retrieved from nytimes.com, courtesy there of artist Chiraag Bhakta.

Across the country, protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death have fueled demands for the removal of statues that symbolize the Confederacy and, for many, the defense of slavery, racism and colonialism. Statues of Christopher Columbus have been dismantled in San Francisco and Richmond, where a legal battle continues over the fate of a Robert E. Lee statue. Just as the protests spread to Europe in a ripple effect, so has the destruction of monuments. One particularly dramatic example was in the English city of Bristol, where protesters toppled a statue of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston, dragged it a third of a mile, and dumped it into the harbor. Assessing monuments in Paris, University of Virginia scholar Marlene Daut has called on French president Emmanuel Macron to remove a statue of slave owner Thomas Jefferson, erected in 2006 in the posh 7th arrondissement.

The toppling of controversial monuments has a long history. According to art historian Erin L. Thompson, for as long as people have been glorifying people and ideas in statues, “other people have started tearing them down.” Beyond symbolic controversies, the statues can place a huge financial burden on taxpayers for the maintenance and security of these monuments. Thompson notes that these funds could be used instead for the preservation of “the amazing sites of African-American history or Native American history,” many of which are “disintegrating from lack of funding.” (We recently posted a story about one such fund, the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, which is dedicated to the preservation of historic Black places in the United States, available here.)

These demands also are affecting museums. The famous equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt outside the Museum of Natural History in New York is coming down. Installed in 1940, the monument includes two figures standing below Roosevelt’s horse: a Native American man on one side and an African man on the other—a clear illustration of racial hierarchy and subjugation.

On the West Coast, the movement has reached the Asian Art Museum (AAM) in San Francisco. The bust of Avery Brundage — the museum patron who began the museum in 1966 with his collection of about 8,000 works of Asian art — has been on prominent display in the museum’s foyer since 1972. Brundage also was known by many as a Nazi sympathizer who espoused racist and anti-Semitic views — “a hateful person,” in the words of museum director Dr. Jay Xu. According to Dr. Xu, the collection was built with a “fetishization of the ‘Orient’ common among white collectors at the time,” and the museum had previously discussed proposal to remove the bust. When the museum eventually reopens after a closure due to the coronavirus outbreak, the bust of Avery Brundage will be gone.

Recent events have also brought to light other ethical concerns surrounding the Asian Art Museum, including the need for thorough provenance research into the Brundage collection. With such research comes the potential restitution of illicitly acquired objects. In a letter to the public published on June 4, Dr. Xu wrote that the museum “must contend with the very history of how our museum came to be” and further, how they should best respond to “a society structured around white supremacy.”

For more on developments at the AAM, see the full New York Times article here.

Summary by Elizabeth Campbell and Courtney Pierce.