Does the Museum of the Bible Hold Modern Forgeries of the Dead Sea Scrolls?

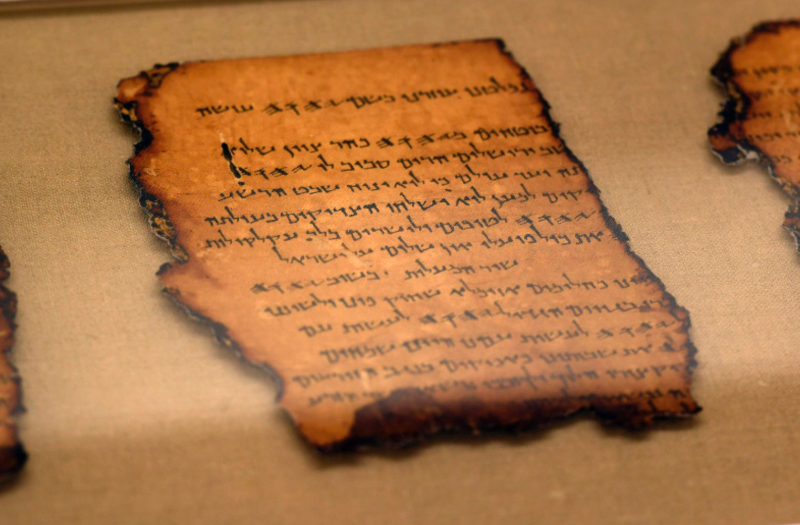

A detailed image of one of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Retrieved from denverpost.com

Commentary

The Museum of Nature and Science in Denver is running an exhibition through September 3, 2018 that features fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, plus more than 500 artifacts from the ancient Middle East. Organized by the Israel Antiquities Authority, the show premiered at Discovery Times Square in New York in 2011 and Denver is the last stop on the U.S. tour.

This is the first time the Dead Sea Scroll fragments have been on display in Colorado, offering visitors an extraordinary opportunity to view the oldest known biblical manuscripts, dating back more than 2,000 years.

Given the religious importance of the biblical texts and their discovery in the West Bank beginning in 1947, it is no surprise that controversy surrounds the ancient manuscripts. Palestinian activists have argued that Israel does not have the right to hold them, prompting the Museum of Nature and Science in Denver to secure an immunity agreement preventing seizure of the objects by the U.S. government.

Elsewhere, different controversies surround alleged Dead Sea Scroll fragments. The ancient manuscripts are exceptionally rare and coveted, and in recent years this acute demand has prompted the proliferation of forgeries on the art market. Even experienced collectors can be fooled by the forgeries, and some experts argue this may be the case with Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby and evangelical founder of the new Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. The Museum, which opened to the public in November 2017, holds thirteen fragments, six of which are currently on display.

For curators and directors of Bible museums, the Dead Sea Scrolls are considered foundational pieces. Biblical scholar and director of the Museum of the Bible David Trobisch told CNN, "Any reputable Bible museum almost has to have Dead Sea Scrolls."

But some experts question the authenticity of the Museum's Dead Sea Scrolls, purchased by the Green family between 2009 and 2014. Kipp Davis, an expert at Trinity Western University, argues that "at least a few" most likely are not authentic, based on analysis of the parchment, handwriting, ink, letter forms, and similarities to modern printed texts. Other experts such as Biblical scholar Emanuel Tov, emeritus professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, argue they have seen no evidence of forgery.

The controversy over the Dead Sea Scrolls is not the first time the Green family has faced scrutiny over its acquisition practices. The U.S. Justice Department recently investigated 5,500 ancient clay tablets acquired by Hobby Lobby that may have been illegally smuggled from Iraq. Green viewed the pieces in a Dubai hotel with a paid art advisor in the summer of 2010 and the family business purchased them for $1.6 million. In a July 2017 settlement with the U.S. government, Hobby Lobby agreed to pay $3 million and return the tablets to Iraq. Green has admitted the purchases should have been handled more carefully.

In the case of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Museum is facing the issue of forgery head-on and commissioned a study of its fragments by a team of researchers, including Davis and Tov. Brill published the findings in 2016.

The Museum of the Bible website also includes information about the order and lot numbers of the original purchase by the Green family. According to the website, the "find-spot for these fragments is unknown," but scientific analysis of the ink and handwriting continues, with results expected "by early 2018." We are still waiting.

Six fragments remain on display in the museum, with a panel acknowledging doubts about their authenticity.

This is a start, but the museum has a long way to go to instill confidence among art experts, the museum community and a broader, well-informed public, which is increasingly aware of ethical issues related to cultural property.