Why the Norton Simon Can Legally Keep Nazi Plunder

Commentary

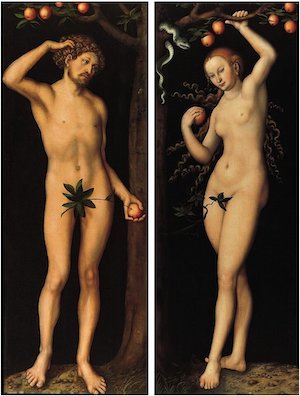

In May 2019, the United States Supreme Court declined to review a Ninth Circuit ruling that the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California has proper title to two artworks plundered by the Nazis. The works in question are a pair of sixteenth-century Adam and Eve wood panels by Lucas Cranach the Elder, once owned by Jewish Dutch dealer Jacques Goudstikker. A specialist in Old Masters based in Amsterdam, Goudstikker had purchased the panels in 1931 at a Berlin auction of artworks held by the Soviet Union. He was a world-renowned dealer and by the beginning of the Second World War had a stock of more than a thousand paintings. While fleeing the Nazis by ship in May 1940 with his wife Desiree and infant son Edward, he died tragically after falling through an open deck hatch. Grief-stricken, Desiree made burial arrangements in Falmouth, England and after a brief stay in Liverpool, secured visas to continue on with Edward to the United States.

Back in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, the Cranach paintings were among several hundred works sold by the dealership employees to Hermann Göring and German dealer Aloïs Miedl. After the war, Desiree negotiated the restitution of some recovered assets, but the Cranach paintings were among those she did not claim, due to recovery fees imposed by Dutch authorities for assets sold to the enemy. The Dutch government held the paintings in trusteeship until 1966, when it sold them to a member of the Russian aristocracy, George Stroganoff-Scherbatoff, who claimed the works had been plundered from his family by the Bolsheviks. Though not convinced the works had truly belonged to the Russian family, Dutch authorities were willing to sell the pieces to Stroganoff-Scherbatoff, who then sold them to museum founder Norton Simon in 1971.

In the late 1990s, Goudstikker heir Marei von Saher—Edward’s widow—relaunched the family’s effort to recover plundered assets. And she has been highly successful. In February 2006, the Dutch government agreed to return more than two hundred Old Master paintings, including works by Jan van Goyen, Salomon van Ruysdael, Jan van der Heyden, and Gerard ter Borch. The family sold most of the pieces, but as Von Saher told the New York Times in 2008, her claim “was never about the money.” It was about belated justice.

Her twelve-year legal battle with the Norton Simon, however, appears to have ended with the Ninth Circuit confirmation of the museum’s clear title. A key issue in this case was whether U.S. courts could contest the decision of the Dutch government to sell the pieces to Stroganoff-Scherbatoff. Lawyers for the museum argued that the act of state doctrine prevented U.S. courts from questioning that decision and, subsequently, conveyance of title to Stroganoff-Scherbatoff. For her part, Von Saher challenged the transfer of title by arguing that the Soviets had seized the paintings from a church in Ukraine, not the Stroganoff family. The case wound its way from district court to the Ninth Circuit—three times—and the U.S. Supreme Court twice declined to hear it.

The Norton Simon’s legal victory underscores the ways in which the law can favor current possessors, even when both sides recognize that artworks in question were plundered by the Nazis, with a known prewar owner and living heirs. Non-binding international proclamations of goodwill aimed at easing Holocaust-era asset restitution, reiterated repeatedly since the 1998 Washington Principles, often have little bearing in courts of law. As for legal measures, the U.S. Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act of 2016 established a uniform statute of limitations in claims to Nazi-plundered objects (six years after a claimant’s actual discovery). But Von Saher’s case illustrates the continued challenges for claimants in the American court system beyond statutes of limitations, including the high cost of litigation.

In the largely private U.S. museum system, it is up to boards of trustees to weigh legal and ethical dimensions of restitution claims, and when appropriate, seek resolutions considered just by all parties. Museumgoers and donors can further insist that the institutions they support are carrying out necessary provenance research, and holding works in the public trust with transparency and integrity.