Who are the Military Mujeres?: History Professor’s New Book Spotlights Latina Women in World War II

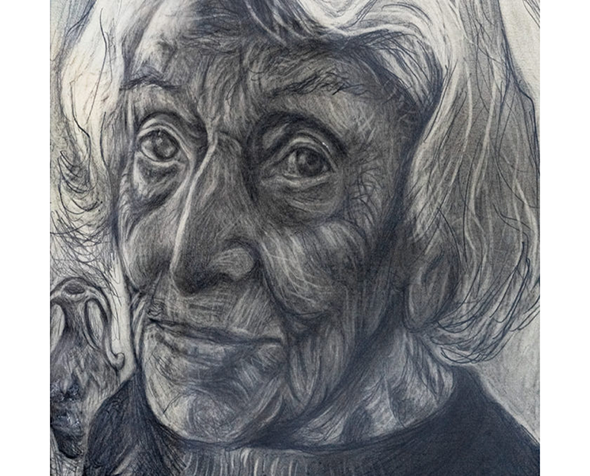

Growing up, Elizabeth Escobedo recalls never seeing the Mexican American side of her family portrayed in classrooms or textbooks; it was, however, her own family’s storytelling that fostered her love of history.

Escobedo is an associate professor of Latina/o history, with a specialization in 20th century Mexican American history, in the Department of History at the College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences. She is currently writing a new book, “Military Mujeres: Mexican American and Puerto Rican Women in the World War II U.S. Armed Forces,” which she will continue to work on this summer with the help of a research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

Escobedo’s father and several of her uncles served in the U.S. military. As well, the women of her family shared memories with her about how their lives changed during World War II, which further inspired Escobedo to take up this newest project.

“Although [my Aunt Ida] and my Aunt Ernie worried daily about their brothers’ safety overseas, they also reveled in new work and leisure roles, finding within the horrors of war a new sense of individuality and independence,” Escobedo said.

This isn’t the first time Escobedo has researched Latinas’ involvement in World War II. Her first book, “From Coveralls to Zoot Suits: The Lives of Mexican American Women on the World War II Home Front,” explored how the wartime environment specifically impacted those of Mexican American descent. Despite continued inequality, well-paid defense jobs afforded daughters of immigrant parents new economic independence and opportunities to broaden their social worlds and experiment with youth culture. They met the call to support the U.S. while also going “against the norms of their family and dating outside of the community — these were pathbreakers in their own right,” Escobedo said.

For her upcoming book, Escobedo described many reasons that Latina women sought to serve in the U.S. military, including patriotism, socioeconomic mobility and as a way to fight patriarchal norms. Even so, Latina women, especially Black Puerto Rican women, were stigmatized and had to navigate racism and colonialism, on top of the sexism that pervaded the military, Escobedo says.

Women of color who sought to enlist, Escobedo says, were denied at first and later met with “suspicion, resistance, and unequal treatment,” regardless of U.S. citizenship or dedicated military service. Puerto Rican women suffered from discriminatory treatment and a continued status as foreign, colonial subjects in the eyes of the U.S. military establishment.

Yet, these stories of struggle and determination are almost unheard of in the plethora of literature surrounding World War II.

“So often the veteran experience is considered solely a male experience, in spite of the many contributions of women to the U.S. military,” Escobedo says.

As such, her research hasn’t been without its difficulties. Escobedo expressed the frustration that comes with researching often overlooked communities in traditional sources. However, she also says it was “part of the fun” to unearth important stories from little pieces of evidence.

This led her to a vast array of sources, including military personnel files, government records, continental and Puerto Rican newspapers, oral histories from the VOCES Oral History Project Archive, and memoirs and photographs from veterans.

Focusing on Puerto Rico specifically has been an exciting element of Escobedo’s research. Not only is it a region that she has consistently taught in her classes, but it is also “a focus that allows me to engage more deeply in the messiness of race for the Latinx community,” Escobedo says.

Escobedo says she was particularly intrigued by the story surrounding Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s mother, Celina Baez. By lying about her age, serving in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during WWII and meeting Sotomayor’s father in the process, Baez set in motion a series of events that eventually led to her daughter being sworn in as the United States’ first Latina Supreme Court Justice.

“There’s not a more American story than that,” Escobedo said.

With the help of the NEH award, Escobedo is spending the remainder of her sabbatical continuing to document the wartime experiences of Afro-Puerto Rican women. Escobedo says she will be traveling to Puerto Rico to visit with the daughter of one Black Puerto Rican women who served in the WAC, Blanca Vasquez, who trained in Fort Des Moines, Iowa. Through this connection, she hopes that together they can uncover more about the family and their personal archival collection, directly fighting against the systemic erasure of an important community during WWII.

Escobedo says she hopes her new project will resonate with the population today “that is living with the ongoing consequences of war and grappling with the obligations we owe to all veteran populations,” while also helping readers “think about the ways in which race is constructed in different ways at different times, affecting communities of color unevenly.”