Professor’s Portrait Captures the Resilience of a Holocaust Survivor

This article appears in the spring issue of University of Denver Magazine. Visit the magazine website for bonus content and to read this and other articles in their original format.

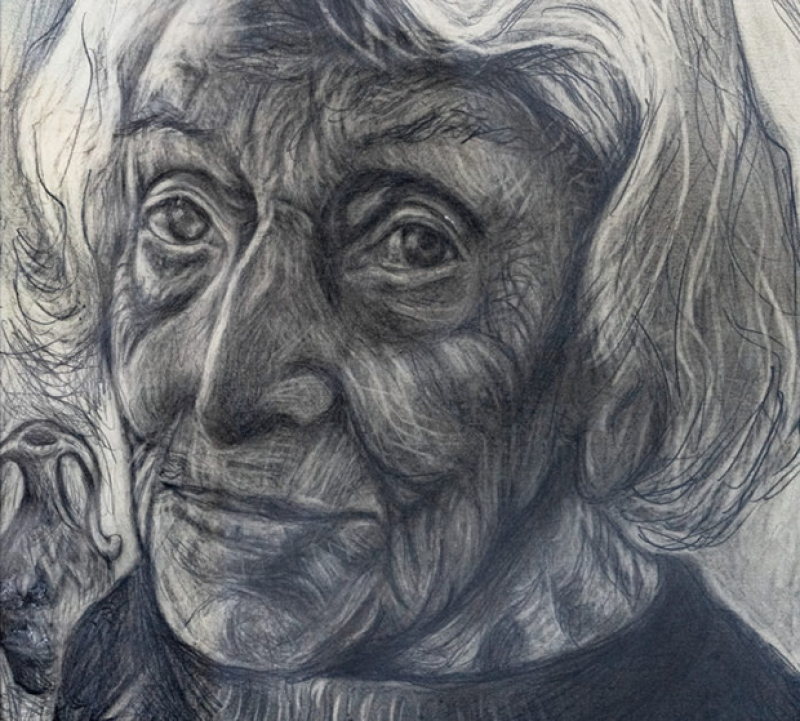

Fourteen years after meeting ceramicist Trudy Strauss, artist and professor Deborah Howard’s new portrait of the Holocaust survivor is on display in DU’s Anderson Academic Commons.

Accompanying a selection of Strauss’ ceramic works, Howard’s portrait is the 26th in her project titled “Child Survivors of the Holocaust.” The project was inspired by a conversation with a student about depictions of aging in portraiture, Howard says.

Across the works, she sought to capture and portray the lives of child survivors to celebrate their achievements and to ensure that the memory of what they endured is not forgotten.

“I wanted people to know that these people somehow made lives for themselves, and how could they do this? How could they get married? How could they have children? How could they do this? But they did, and they all have different stories,” Howard says.

The first portrait depicted Harry Lopas—Howard’s uncle—who was a hidden child in Belgium during the Holocaust. “Once I got going, it was a hunt to find the people,” she says.

From connections through family and friends to chance encounters at her son’s orchestra recital, an antique store and even at the University of Denver, Howard found, met and tracked down child survivors from 2003 until 2008.

The project’s intent drove her to choose drawing over photography or painting as the medium for her portraits.

“Drawing has a mark and a scribble. My handwriting and my mark making prove that I existed and that I was with that person,” Howard says. “So in a way, I’m a witness that this person really did live. Because I lived, and you know I lived because there’s scribbling in there.”

Beyond capturing her subjects’ faces, Howard incorporated historical knowledge and emotion into each portrait, conveying the lives lived and the suffering and success of each person.

The drawings were to be displayed without a biography or story, Howard notes, because she “wanted people to just look at them, have their name and know from their face that they were there.”

Inclusion in DU’s Ira M. and Peryle Hayutin Beck Memorial Archives, which is dedicated to the preservation of Jewish history and heritage in the Rocky Mountain region, inspired Howard to compile her notes, correspondence and the survivors’ stories so that a written piece could complement each portrait.

More than a decade after her project ended, Howard added the portrait of Trudy Strauss.

As with many of the survivors she drew, Howard met Strauss by chance, when the two were swimming at the Schlessman YMCA more than 20 years ago. In 2009, Strauss learned of the project and asked Howard to draw her. But after meeting with and photographing Strauss, Howard shifted focus to other work without drawing the portrait.

In the summer of 2021, a friend reconnected Howard with Strauss, who was 106 and still living in Denver. Twelve years after initially setting out to draw Strauss, Howard completed the portrait on Jan. 30, 2022.

Strauss’s portrait will join 21 of Howard’s drawings that reside in the Beck Archives. Four other portraits remain in the Holocaust Art Museum at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Israel.