Brent Learned

For me, a place of memory is not only a location. It can be an item, a time, a type of food , the knowledge we gain, or the love we carry. It can be the bravery we show, our thoughts for others, or the hate we hold in our hearts. It can be our heritage and culture or the sacrifices we make. All these are examples of places of memory.

The pieces in this exhibition all tell the story of my ancestors from my tribe the Cheyenne and Arapaho. I use famous works of art to showcase my tribe’s places of memory in a relatable way.

For More of Brent Learned's Art

Brent Learned's Website

Facebook: @brentlearnedart

Instagram: @brentlearned

-

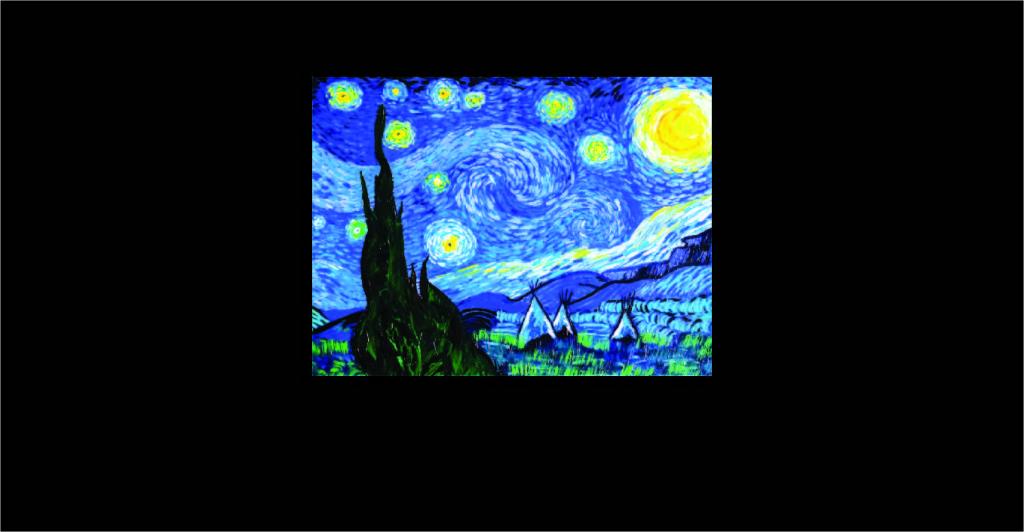

Starry Night on the Plains (ode to Vincent van Gogh). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

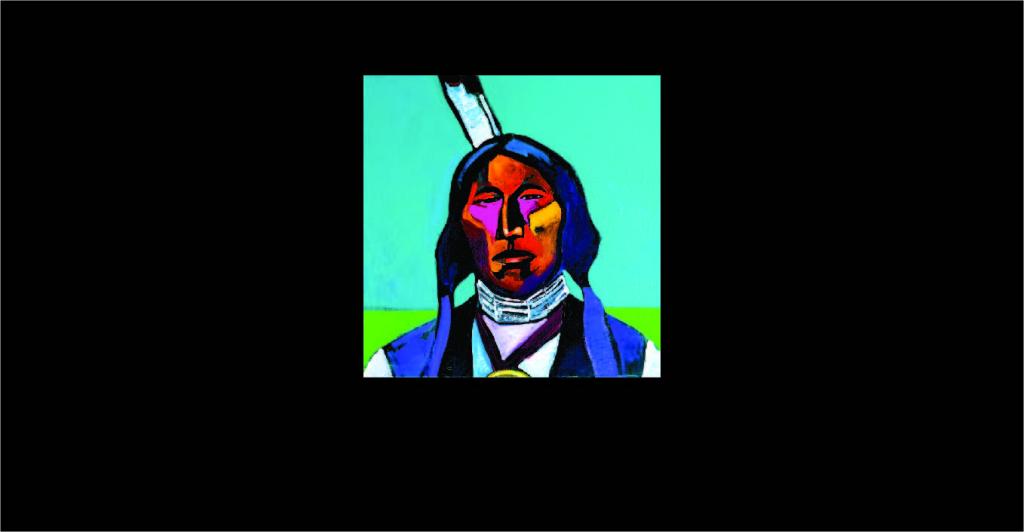

Arapaho Indian. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

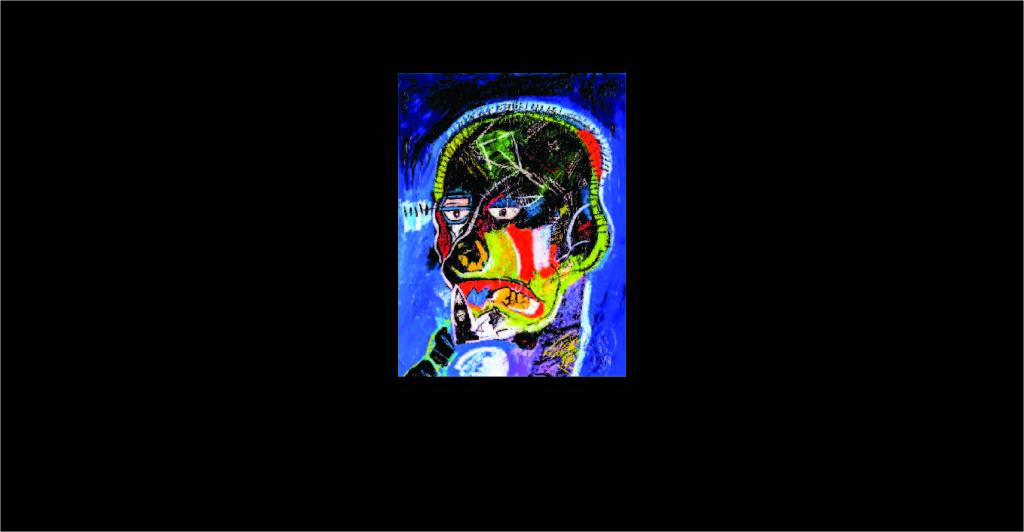

Cheyenne Warrior (ode to Jean-Michel Basquiat). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Cheyenne Medicine (ode to Henri Matisse). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

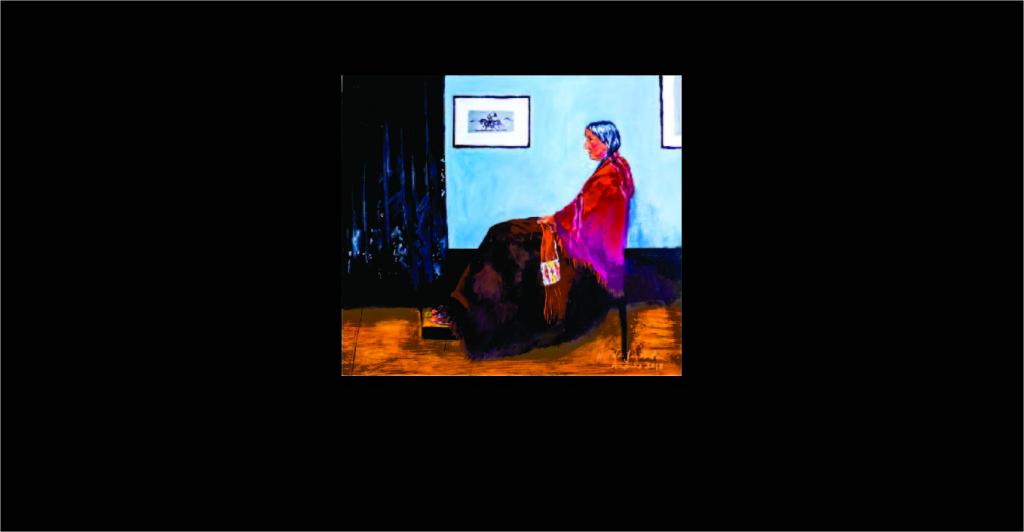

Cheyenne Grandmother (ode to James McNeil Whistler). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

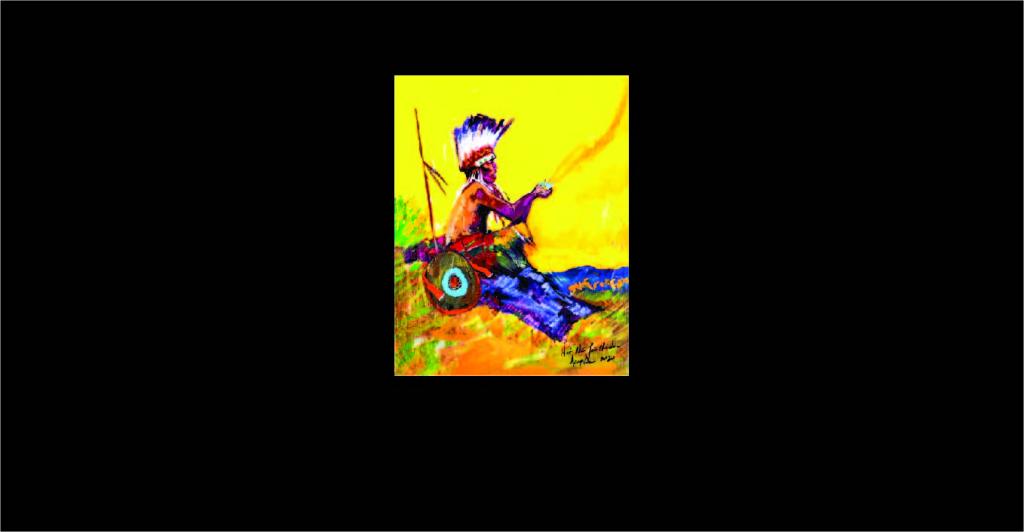

Good Medicine. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

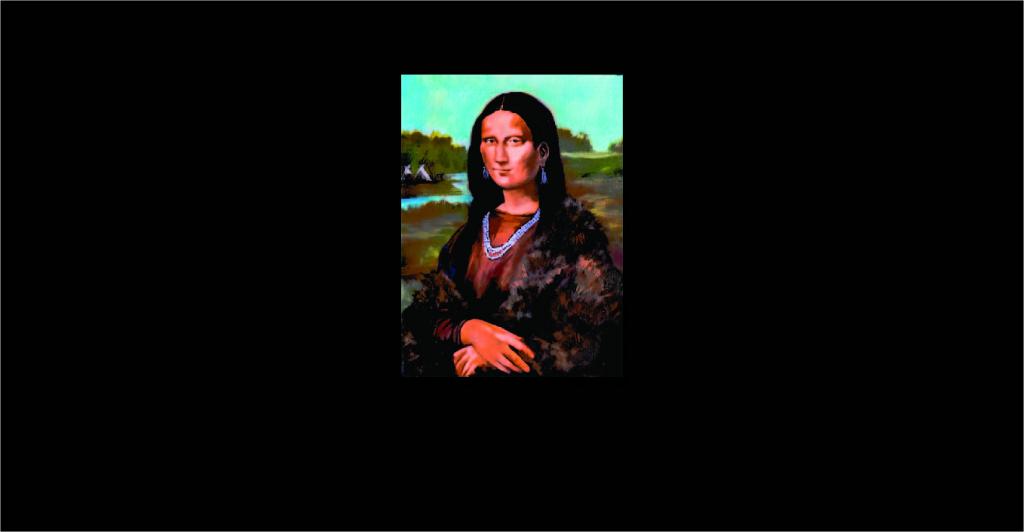

Pretty Nose Arapaho (ode to Leonardo da Vinci). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Genocide Sand Creek Massacre (ode to Pablo Picasso). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

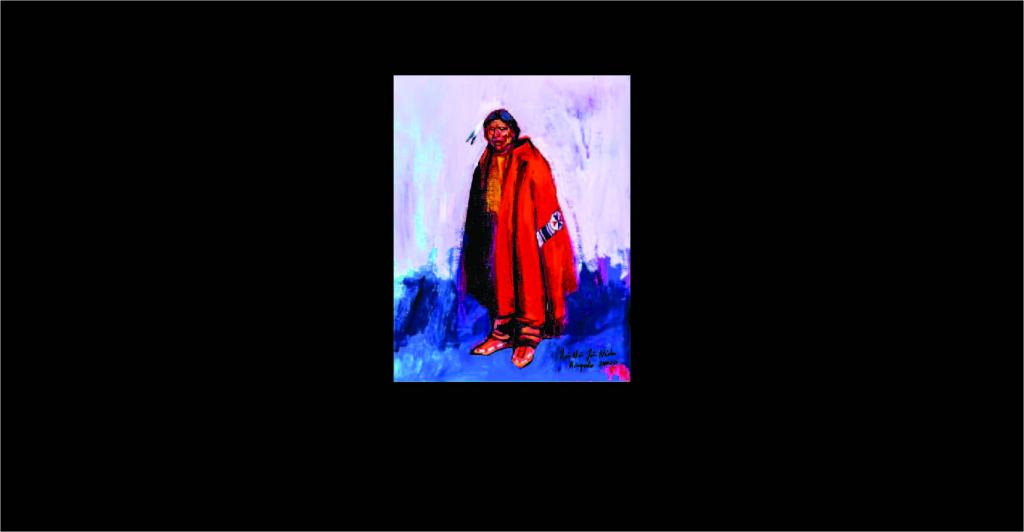

Arapaho Indian with Red Robe. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

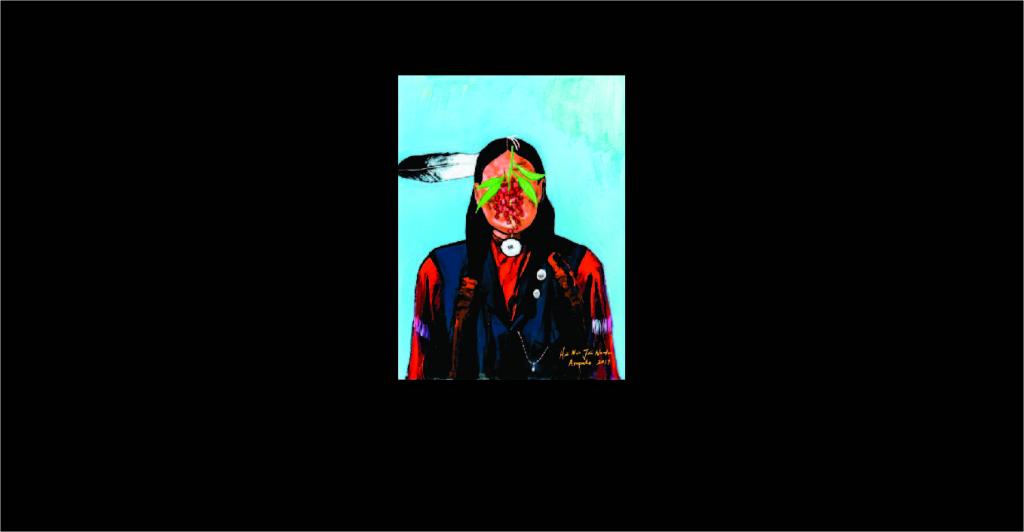

Arapaho with Chokecherries (ode to Rene Magritte). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Buffalo. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Words (ode to Ed Ruscha). Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Arapaho with Mask. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Courtship. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

-

Counting Coup Stealing Horses. Photograph by Madeline Bowen

*Note* If you are having trouble seeing the images in this slideshow, please reduce the width of your browser window

Starry Night on the Plains (ode to Vincent van Gogh), 2018

“Judge not by the eye but by the heart”—Cheyenne Proverb

I painted "Starry Night on the Plains” in the style of Vincent van Gogh’s “Starry Night” (June 1889). The original work depicts the view from the east-facing window of van Gogh’s asylum room at Saint-Remus-de-Provence just before sunrise in front of an imaginary village.

In my take on the painting, it is the night before the Battle of the Washita (November 27, 1868), when Lt. Col. General Armstrong Custer’s 7th U.S Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s Cheyenne camp on the Washita River in what is now Cheyenne, Oklahoma.

Custer's forces attacked the village when scouts found the trail of a party that had raided white settlers there. But that party had passed through—Black Kettle and his people had been at peace and were seeking peace. Custer's soldiers killed women and children in addition to warriors, and took many captives to serve as hostages. Larry Sklenar, in his narrative of the Washita battle, also describes how these "hostages" were also used as human shields:

“Custer probably could not have pulled off this tactical coup at the Washita had he not had in his possession the fifty-some women and children [as] captives. Although not hostages in the narrowest meaning of the word, doubtlessly it occurred to Custer that the family-oriented Cheyenne warriors would not attack the Seventh Cavalry with the women and children marching in the middle of his column.”

Custer himself articulated the military logic for tactical use of human shields in his book "My Life on the Plains", published two years before the Battle of the Little Big Horn:

“Indians contemplating a battle, either offensive or defensive, are always anxious to have their women and children removed from all danger…For this reason I decided to locate our [military] camp as close as convenient to Chief Black Kettle's Cheyenne village, knowing that the close proximity of their women and children, and their necessary exposure in case of conflict, would operate as a powerful argument in favor of peace, when the question of peace or war came to be discussed.”

A place of memory is the evil of some people towards another human being. If we do not learn from the past, we are doomed to repeat it.

.jpg?crop=yes&position=c)

Arapaho Indian, 2020

“When we show our respect for other living things, they respond with respect for us”—Arapaho Proverb

3,000 years ago, the Arapaho-speaking people (Heeteinono'eino') lived in the western Great Lakes region which is now Canada and the Minnesota area. Following westward expansion in eastern Canada, together with the Cheyenne (Hitesiino'), the Arapaho were pushed westward onto the eastern Great Plains.

The Arapaho people entered the Great Plains, the western Great Lakes region, sometime before 1700. During their early history on the plains, the Arapaho lived on the northern plains—from Canada south to Montana, Wyoming, and western South Dakota.

They moved around using a large sledge structure called a travois, pulled by domestic dogs. The Arapaho acquired horses in the early 1700s by trading with other tribes. The Arapaho became a nomadic people, utilizing the horses as pack and riding animals. They traveled more easily by horseback and hunted more widely, increasing their success in hunting on the Plains.

Some of the allies of the Arapaho were Lakota, Comanche, and Kiowa with a strong alliance with the Cheyenne who they treated like brothers.

The Arapaho signed many treaties with the United States government. The last one was the Medicine lodge treaty in which the United States promised the Arapaho and Cheyenne peace and protection from white intruders in return for amity and relocation to reservations in western Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The painting is of an Arapaho Indian remembering where he came from and all the struggles his people went through in life.

His heart is a place of memory.

Cheyenne Warrior (ode to Jean-Michel Basquiat), 2020

“Beware of the man who does not talk and the dog that does not bark”—Cheyenne Proverb

Cheyenne (Tsitsistas) people had six different military societies, one of the bravest of which was the Dog Soldiers, known as the “Spartans of the Plains.” Beginning in the late 1830s, this society evolved into a separate, militaristic band that played a dominant role in Cheyenne resistance to the westward expansion of the United States across the land where the Cheyenne settled in the early nineteenth century—Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

After the deaths of nearly half the Southern Cheyenne in the cholera epidemic of the late 1840s, many of the remaining bands joined the Dog Soldiers. It effectively became a separate band, occupying territory between the Northern and Southern Cheyenne. Its members often opposed policies of peace chiefs such as Black Kettle. In 1869, most of the band were killed by United States Army forces in the battle of Summit Springs. The surviving societies became much smaller and more secretive in their operations.

In the twenty-first century, there has been a revival of the Dog Soldiers society among the Cheyenne people.

“Cheyenne Warrior” is done in a Jean-Michel Basquiat style because, for me, the action and emotion symbolize the chaos that would have marked the life of a Cheyenne Dog Soldier. Knowingly sacrificing oneself to preserve and protect one’s family and tribal members is commendable.

His legacy as one willing to sacrifice himself for others is a place of memory.

Cheyenne Indian (ode to Henri Matisse), 2018

“Our first teacher is our own heart.”—Cheyenne Proverb

The Cheyenne (Tsitsistas) people are split into two federally recognized nations the Southern (the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma), and the Northern Cheyenne (in Montana). They are close allies with the Arapaho and loosely aligned with the Lakota. They migrated west in the early 18th century as white settlers pushed West across the plains and adopted the horse culture through trade with other Plains tribes.

The Cheyenne settled in the Black Hills (present day South Dakota) and introduced the horse culture to the Lakota bands living there in the late 1730s. Allied with the Arapaho, they first forced the Kiowa into the Plains and were eventually forced south and west by numerous Lakota. The unified Cheyenne people began to create and expand into a territory of their own and made a formal alliance with the Arapaho people.

The Cheyenne people were once composed of ten bands that spread across the Great Plains from southern Colorado to the Black Hills in South Dakota. They fought their traditional enemies, the Crow, who fought with the United States against some of the Plains Indians. In the mid-19th century, the bands began to split, with some choosing to remain near the Black Hills, and others choosing to remain near the Platte rivers of central Colorado. Sweet Medicine, a Cheyenne prophet, predicted the coming of the horse, the cow, the white man, and other new things to the Cheyenne.

After numerous battles with other tribes on the plains and the United States government, the Cheyenne were eventually relegated to reservation life in Oklahoma and Montana.

“Cheyenne Indian” is done in the style of Henri Matisse. The stars represent his ancestors watching over him. The Cheyenne symbol on his chest represents his heart, the love of being who he is and the pride of the ones that came before him.

His love of his tribe and his culture is a place of memory.

Cheyenne Grandmother (ode to James McNeill Whistler), 2018

“It's not good for anyone to be alone.”—Cheyenne Proverb

“Cheyenne Grandmother” is a painting done in James McNeill Whistler’s style with a grandmother sitting in a chair before an image of her husband. It is a take on “Arrangements in Gray and Black Number #1” (also known as “Whistler’s Mother”). In my version, she is a grandmother.

She is reminiscing about her loved ones and holding a relic—her husband’s tobacco bag—that reminds her of her past, wishing he were there beside her.

An item that reminds her of someone special is her place of memory.

Good Medicine, 2020

“Take only what you need and leave the land as you found it.”—Arapaho Proverb

“Good Medicine” shows a Cheyenne man seated outside and smoking sage to cleanse himself from any bad medicine that came his way. Being Cheyenne and Arapaho, I was always taught that we are here to preserve the land. We do not own it but pass it on to the next generation.

The plants and animals are here for us to live in harmony. We come from the dust, and we go back to the dust—the cycle of life.

Places of memory are all around us. If we listen to all living things as they will listen to us.

Pretty Nose Arapaho (ode to Leonardo da Vinci), 2021

“When there is true hospitality, not many words are needed.”—Arapaho Proverb

Pretty Nose was an Arapaho woman and a brave fighter. She was identified as Arapaho by her red, black, and white beaded cuffs.

Pretty Nose took part in The Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1867, (Iokata to the Cheyenne and The Battle of the Greasy Grass to the Arapaho), where General Armstrong Custer, the leader of the 7th calvary, lost his life.

Pretty Nose lost loved ones on this battlefield, a place that is known as the greatest victory of Native people against the United States Army.

I painted Pretty Nose as a western style “Mona Lisa,” considered by most experts one of the most important works of art that Leonardo da Vinci ever did.

The people she lost in battle at the Greasy Grass are a place of memory.

Genocide Sand Creek Massacre (ode to Pablo Picasso), 2021

“Our pleasures are shallow; our sorrows are deep.”—Cheyenne Proverb

On November 29, 1864, 675 men from the third Colorado Calvary under the leadership of John Chivington attacked a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado Territory. They killed and mutilated an estimated 70 to 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians about two-thirds of whom were women and children. Chivington's men ignored the U.S. flag and a white flag that Black Kettle, a Cheyenne peace chief, flew to show that they were not hostile.

"I saw the bodies of those lying there cut all to pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before; the women cut all to pieces ... With knives, scalped; their brains knocked out; children two or three months old; all ages lying there, from sucking infants up to warriors ... By whom were they mutilated? By the United States troops." — John S. Smith, Congressional Testimony of Mr. John S. Smith, 1865

"I saw one squaw lying on the bank, whose leg had been broken. A soldier came up to her with a drawn sabre. She raised her arm to protect herself; he struck, breaking her arm. She rolled over, and raised her other arm; he struck, breaking that, and then left her without killing her. I saw one squaw cut open, with an unborn child lying by her side." — Robert Bent, New York Tribune, 1879

"There was one little child, probably three years old, just big enough to walk through the sand. The Indians had gone ahead, and this little child was behind, following after them. The little fellow was perfectly naked, traveling in the sand. I saw one man get off his horse at a distance of about seventy-five yards and draw up his rifle and fire. He missed the child. Another man came up and said, 'Let me try the son of a b-. I can hit him.' He got down off his horse, kneeled down, and fired at the little child, but he missed him. A third man came up, and made a similar remark, and fired, and the little fellow dropped." — Major Anthony, New York Tribune, 1879

"Fingers and ears were cut off the bodies for the jewelry they carried. The body of White Antelope, lying solitarily in the creek bed, was a prime target. Besides scalping him the soldiers cut off his nose, ears, and testicles-the last for a tobacco pouch." — Stan Hoig

"Jis' to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws and blew the brains out of little innocent children. You call such soldiers Christians, do ye? And Indians savages? What der yer s'pose our Heavenly Father, who made both them and us, thinks of these things? I tell you what, I don't like a hostile red skin any more than you do. And when they are hostile, I've fought 'em, hard as any man. But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who would." — Kit Carson Col. James Rusling.

Sand Creek was one of the biggest and most tragic wars between the Indians and the United States government. The painting, done in a Pablo Picasso style, offers my take on his most famous painting “Guernica.” I call my piece “Genocide Sand Creek Massacre.”

It hints at the concept of Manifest Destiny through the woman holding a torch. The American flag and a white flag show that the people at Sand Creek were not hostile. They highlight the emotion and trauma of the devastation that happened that November 29 day.

Sand Creek is a physical place of memory. For the Cheyenne and Arapahoe people it is a place of mourning for the lives lost that day.

.jpg?crop=yes&position=c)

Arapaho Indian with Red Robe, 2020

“If we wonder often, the gift of knowledge will come.”—Arapaho Proverb

The term “Indian Giver” is now often used as a pejorative expression to describe someone who gives a gift and later wants it back. But this meaning has been twisted and misconstrued over time. The original term meant that if you showed me respect and honor, I would give the same to you, even giving you the shirt off my back.

Among the Plains Indians, it is a high honor to receive a blanket, as no matter where one goes, one always needs to be kept warm. The red robe in this image represents that respect and honor.

The knowledge that one has earned the respect to be honored with such a gift is a place of memory.

Arapaho with Chokecherries (ode to Rene Magritte), 2017

“Before eating, always take time to thank the food.”—Arapaho Proverb

“Arapaho with Chokecherries” is my take on a painting done by Rene Magritte called the “Son of Man” (also known as “Man with Apple”)—perhaps his best-known painting. My version shows an Arapaho Indian with chokecherries where Magritte painted an apple.

Why chokecherries? Because apples are not indigenous to North America. They were brought here by the Europeans in the 17th century. Chokecherries were abundant on the Plains and a major food source for the Plains Indians.

Food is a cultural place of memory and reminds us of our connection to our ancestors.

Buffalo, 2021

"When you lose the rhythm of the drumbeat of God, you are lost from the peace and rhythm of life.”—Cheyenne Proverb

The Buffalo was everything to the Plains Indians. Plains Indian tribes survived on hunting all types of game, but the Buffalo was their main source of food and had over 100 other uses. They used every part of the Buffalo and wasted nothing.

Skins became tipis and clothing, and horns became tools, like scrapers. Hides became robes, shields, and ropes, and hoofs became glue. Sinew and muscle became bowstrings, moccasins, and bags. Even dried dung became fuel.

Plains Indians followed the seasonal migration of the Buffalo in their tipis, sometimes fighting with other tribes over hunting grounds. They only hunted what they needed for food, and never without a ceremony. Killing a Buffalo without the permission from the elders of the tribe would bring bad medicine on to the tribe and often led to banishment.

The deep meaning the Buffalo hold to the people on the Plains is a place of memory. We will never forget what the Buffalo meant to us—life itself.

Words (ode to Ed Ruscha), 2021

“Take only what you need and leave the land as you found it.”—Arapaho Proverb

As caretakers of the land, we are only here for a short time and only use what we need, leaving the rest for the next generation.

This belief rang true for generations of Indians on the Plains, until the white man’s westward expansion. They justified the expansion through manifest destiny—a widely held belief in the 19th century United States that white settlers were destined to expand across North America, and had a God-given right to get rid of the Indigenous people who lived there.

It destroyed and dismantled Native cultures, heritage, and languages.

My mother and father taught me that you must know where you came from to know where you are going in life. One must understand the past to recognize the present.

The heritage and culture that can never be taken from me are a place of memory.

Arapaho with Mask, 2020

"Do not judge your neighbor until you walk two moons in his moccasins.”—Cheyenne Proverb

As the COVID-19 pandemic raged, I saw tribes across the country suffering, including severe loss of life in the Navajo Nation.

When I lost several friends to the virus, I wanted to help others by sharing the message that the virus needed to be taken seriously to protect our elders.

I created a series of paintings highlighting the importance of social distancing, washing hands, using hand sanitizer, protecting our elders, and wearing a mask. “Arapaho with a Mask” was one painting from that series.

Thinking of others during stressful times is a place of memory.

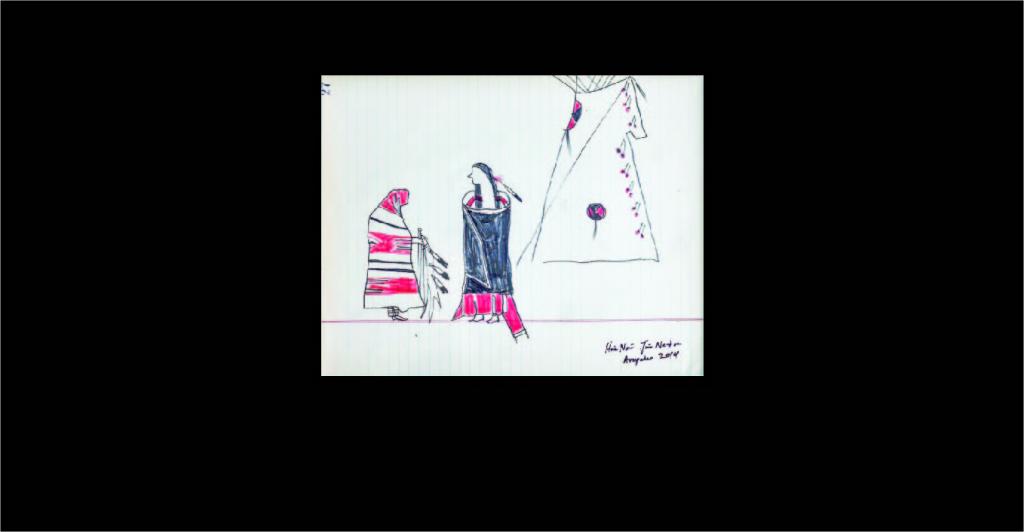

Courtship (Ledger Art), 2014

“Each bird loves to hear himself sing.”—Arapaho Proverb

Ledger artwork shows a narrative drawn or painted on paper or cloth. In the late 19th century, accounting ledger books were a common source of paper for Plains Indians.

One of the first known ledger drawing came from a young Cheyenne boy who was a prisoner at Fort Marion in Florida. I created this piece in a traditional Cheyenne style drawing of a man and a woman going through courtship.

The place where they first fell in love is a place of memory.

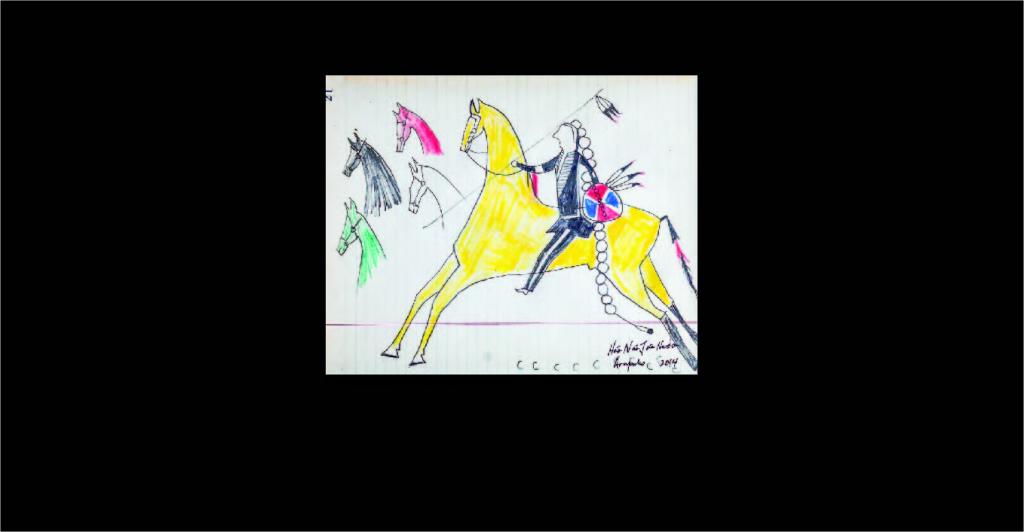

Counting Coup Stealing Horses (Ledger Art), 2014

“If a man is as wise as a serpent, he can afford to be as harmless as a dove.”—Cheyenne Proverb

When Plains Indians won prestige against an enemy, it was known as counting coup. Any blow struck against the enemy counted as a coup, but the most prestigious ones included touching an enemy warrior with a hand, bow, or coup stick and escaping unharmed.

Other coups included touching the first enemy to die in battle or touching the enemy's defenses. In some nations, riding up to an enemy, touching him with a short stick, and riding away unscathed also counted.

Risk of injury or death was required to count coup. Escaping unharmed while counting coup was considered a higher honor than being wounded in the attempts. These acts of bravery were often recorded and retold as stories. In this piece, I recorded the stealing of an enemy’s horse.

This bravery before the enemy is a place of memory.

Meet the Artist

Brent Learned

Brent Learned is an award winning and collected Native American artist who was born and reared in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. Brent graduated from the University of Kansas with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts, Spring of 1993.

“I’m an artist who draws, paints and sculpts the Native American Indian in a contemporary style. I have always appreciated the heritage and culture of the American Plains Indian. I try to create artwork to capture the essence, accuracy, and historic authenticity of the American Plains Indian way of life. Although I have many different styles, I’m typically known for the use of bold vibrant colors in my depictions of the American Plains Indian.”

Learned has a passion for being active in the community. He was one of the curators of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum’s Wintercamp Show, which aimed to give new artists in the community an opportunity to show their work. This was the first all Native American show to feature contemporary Oklahoma Native American art. Learned was also the lone curator of Native Pop which featured today’s contemporary pop indigenous visual artists. It was the first of its kind and has since traveled all over the United States.

Learned has also had the honor of working with some of the top artists in the contemporary art world, including a collaboration with Dale Chihuly’s team on the Eleanor Blake Kirkpatrick Tower, Chihuly’s tallest installation to date, in the Oklahoma City Art Museum. He also shared his culture and heritage while traveling abroad, including an artist residency at Strathnairn in Canberra, Australia where he collaborated with Aboriginal painter Merryn Apma to create several paintings as well as workshops and lectures.

He also participated in a cultural exchange program between the University of Oklahoma and the US Embassy to strengthen ties between the indigenous people of North America and the Buryat people of Siberia, Russia. During that program, Learned collaborated with an artist from Irkitsk, Russia to publish a children’s book, and was inspired by the ways his partner’s creative approach was influenced by Buryat history, culture, and relationship to nature. “Cultural preservation,” Learned observed, “drew us together on how we as indigenous people can preserve what’s left of who we are and carry it on to the next generation.” Workshops with local communities, and a collaborative exhibition and presentation were among the partnership’s most memorable events for Learned.

Learned’s work resides in museums around the nation including the Smithsonian Institute-National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., the Cheyenne/Arapaho Museum in Clinton, Oklahoma, the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, and the University of Kansas Art Museum in Lawrence, Kansas as well as numerous private collections. He currently resides in Oklahoma City. His artwork can be viewed at www.buffalobullhowling.com, www.facebook.com/brentlearnedart, and www.instagram.com/brentlearned

Media Mentions

- The Oklahoman - Merging Tribal culture with Pop Art Sensibilities

- The Oklahoman - Exhibit at Chisholm Trail Heritage Center

- The Oklahoman - Music video for Redbone's 1970s hit 'Come and Get Your Love'

- The Art Newspaper - First official music video for Redbone

- PBS - Pop art with a Plains Indian perspective

- The Lawton Constitution - Virtual exhibit tour

- Oklahoma Arts Council - State Art Collection

- Oklahoma Gazette - Native Pop! Art Show

- Oklahoma Gazette - “People think, ‘Oh, well, it’s been done,’ but no, it hasn’t…

- Sun Sentinel - On tribal lands, a time to make art for solace and survival

- New York Times - Native American Art and Coronavirus

- Indian Country Today - ‘Raw, In-Your-Face’ Native Pop Art

- Indian Country Today - Native artists lend skills to COVID-19 campaigns

- Indian Country Today - Why 'Come and Get Your Love' now?

- Indian Country Today - Groundbreaking Nude Exhibit

- Indian Country Today - Painting in Moscow

- Red Cloud Indian School - “Native Pop” Introduces Pine Ridge Students to New De…

- On the trail of DNA. How the Indians looked for a common ancestor with the Bury…

- The Russian American - How the Oklokhom Indians and Buryats were looking for a …