Connecting the Pieces

Dialogues on the Amache Archaeology Collection Online Exhibit

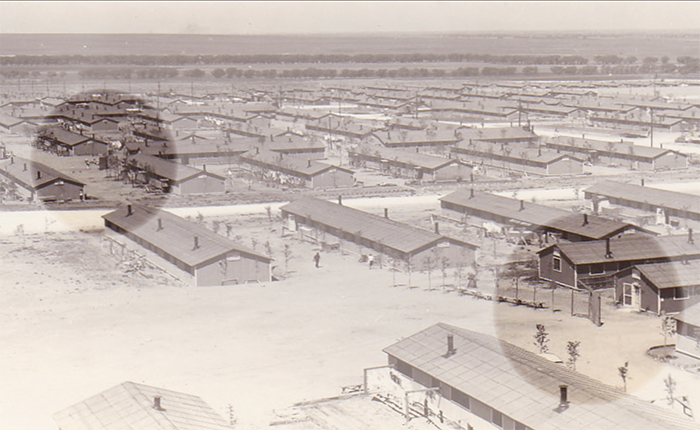

Colorado's tenth largest city during World War II was Amache, a one-mile square incarceration facility surrounded by barbed wire, guard towers, and the scrub of the High Plains.

Over the course of three years, over 10,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry lived there, yet their experience is muted in our national discourse. The objects in this exhibit, fragments of those uprooted lives, encourage dialogue about this history.

This exhibit was created as part of the DU Amache Project, engaging University of Denver students, scholars and community members. The curators, community members and University of Denver students chose these objects because of the history they reveal and the stories they help us tell.

This exhibit was created at the University of Denver as part of Dr. Bonnie Clark's American Material Culture Course, Spring Quarter 2015, as well as the DU Amache project. Exhibit design by Halena Kapuni-Reynolds and Anne Amati. Exhibit photography by Orla McInerney and Mason Seymore.Thank you to the students and community members who gave their time and shared their voices: Cassandra Cortright and Mary Ann Amemiya, Megan Debard and Gil Asakawa, Trevor Gilbert-Mayes and Ann Yoshihara-Murphy, Kelley Rankins and Linda Takahashi Rodriguez, Todd Savolt and May Murakami, Mason Seymore, Millie Morimoto King, James Knoblauch and Cassidy King, Olivia van den Berg and Erin Yoshimura. This exhibit is funded in part by a State Historical Fund grant award from History Colorado.

Amache Collection

-

Amache Project

Amache Project

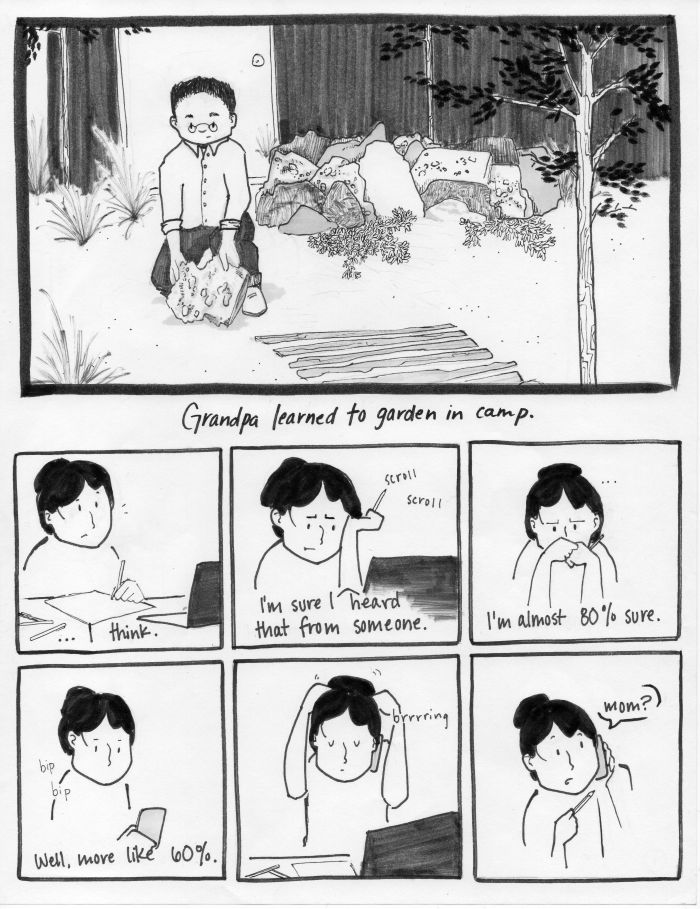

Since 2005, the University of Denver Anthropology Department has been involved in researching, interpreting, and preserving Amache. The keystone of the project is a collaborative summer field school, held every other year since 2008. In the field, participants practice archaeology at the site and work in the Amache Museum to preserve and interpret the tangible history of Amache.

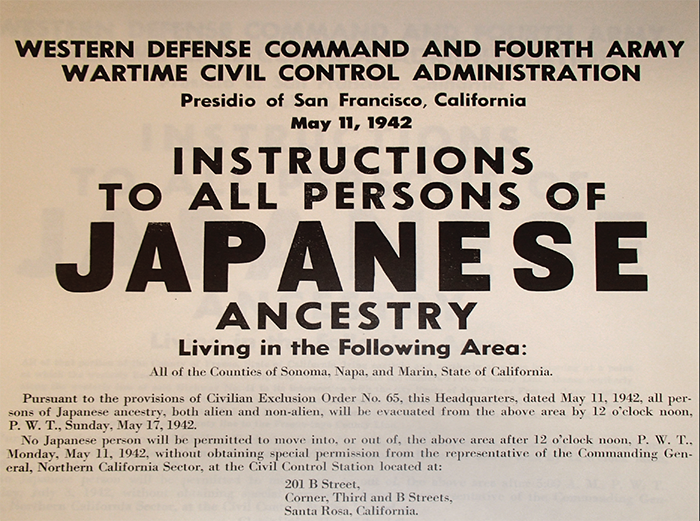

Volunteers, both at Amache as young girls, screen soil from excavations. Courtesy of the DU Amache Project. Conducting archaeology at a site occupied from 1942 to 1945 seems counterintuitive. Surviving government records document the forced relocation of Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes along the West Coast. Photographs depict families gathering what they could carry– hurrying to sell, destroy, or store other belongings in the week they had to prepare. People remember their expulsion and confinement, first in the assembly centers, then in War Relocation Authority incarceration facilities, like Amache.

Washing finds during a community open house at the museum. Courtesy of the DU Amache Project. Yet even with this rich documentary and oral record, archaeology reveals the rhythms of daily life in the camps–games played to pass the time or forget, gardens planted to beautify the stark military landscape, materials repurposed to improve living conditions. These objects recovered from Amache provide a different way to encounter this experience, a physical connection to an unthinkable American episode.

Archaeologists recovered these objects during research at Amache in 2012 and 2014. War Relocation Authority Amache site plan. Courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration. More information on the DU Amache Project: portfolio.du.edu/amache

-

Abalone

Abalone Shell Fragment

Seashell, 2.75" wide. Found in Block 11H. Native to the coast of California, this abalone shell may have served as a reminder to Japanese Americans living in Amache of their West Coast roots. Cut on one side, it might have been used for arts and crafts in camp or to decorate a garden. Japanese families could have brought abalone shell with them from California or purchased it at the Granada Fish Market. The Granada Fish Market offered a variety of traditional foods found in small Japanese markets such as seafood, chicken, soy sauce, and noodles. The abalone shell, along with other traditional groceries delivered from the Granada Fish Market, provided an outlet for Japanese people living in Amache to express a culture that government policies often suppressed.

- Todd Savolt, DU Student Curator

Building on his pre-war expertise, Frank Tsuchiya left Amache to start a business in nearby Granada. The Granada Fish Market, pictured here, was so successful that it spawned two post-war markets, one in Denver and one in Los Angeles. Courtesy of Jack Muro, Japanese American National Museum collection.

Complete example of an abalone shell found in an Amache garden. Courtesy of the DU Amache Project. Personal Reflection

This piece of abalone shell collected on the surface in block 11H brought back memories of pre-World War II for me. My mother always included abalone among the many foods prepared for New Year's Day.

The abalone shell had a row of perforations along one side and was lined with mother of pearl. It was beautiful and I wanted to keep it for myself. The abalone meat was very rubbery and chewy, but we enjoyed it. I, myself, do not ever recall eating it in Amache.

- May Murakami, Community Curator. May lived with her family at block 7H at Amache.

Example of intact abalone shell from DMNS. Photo by DUMA. May's Amache Story

My parents, Joichi and Yu Yasumura, were both born in Hiroshima, Japan. My sisters (Mary, Tomoe, Grace, and Lily), my brothers, (Edward and William) and I were all born in California. Our lives, as well as other Japanese Americans, were changed forever when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066 on February 19, 1942, which paved the way for the internment of Japanese Americans.

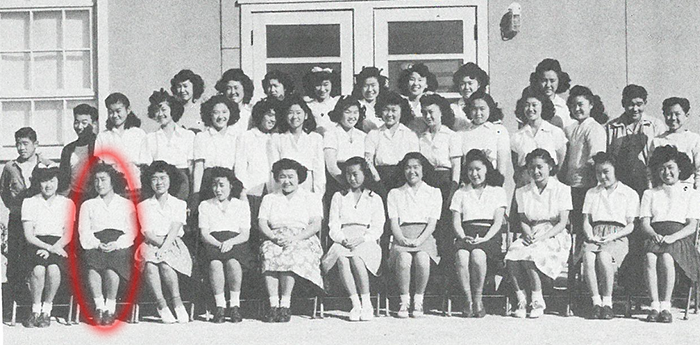

May at Amache HS, Sophomore, AHS Yearbook, 1945. As ordered, on May 22, 1942 (my brother Eddie's birthday) our family went to the Merced Assembly Center which was on the Merced County Fair Grounds. The barracks we were assigned to were located at the edge of the camp and a guard tower was right outside our room. A fence was right behind our barracks and a grape vineyard was behind the fence. We were at the Merced Assembly Center for about three months, leaving for Granada towards the end of August 1942.

The first group of internees from the Merced Assembly Center arrive in Granada. They boarded waiting buses and trucks for the ride to Amache. Courtesy of the National Archives & Records Administration. After being on the converted coal train for three and a half days, we arrived in Granada at night. A bus took us to Amache. The barracks we were assigned to (7H) had no electricity yet. We were tired and grimy so were asked if we wanted to shower and we said "yes." We proceeded across an open block with a lantern or flashlight to the "shower" building and found only cold water. Somehow we managed to clean ourselves and returned to our dark new home. In the morning, we looked outside and saw this large expanse of nothingness – no trees, shrubs or plant life of any kind.

My two oldest sisters had completed high school so they sought jobs in camp and found some by inquiring where signs were posted "help wanted." My father got a job as a cook but at another block. He had been a cook at Merced. Prior to evacuation he was a truck farmer. The rest of the five children were students. I attended 8th grade in the barracks and 9th and 10th grade in the new high school. I remember walking backwards up the hill to fend off the wind and sand. My friends and I joined the girl reserves of the YWCA and spent most of our time going to school and the Y club called Gamma RHOS, which was a service club. Those of us who took typing and shorthand got jobs at the administration building.

May with fellow Girls Athletic Association Members, Amache High. Onlooker, AHS Yearbook, 1945. On August 15, 1945, one day after V day, our mother, brother William, myself, Grace, and Lily left Amache for Denver. My brother Eddie had left camp in 1944 for Denver and eventually joined the Airborne Paratroopers and was still in the service. Unfortunately, he was not sent overseas during the war but was in service during occupation in Europe.

Last of the Amache internees awaiting train departure to western United States. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records. My mother, two younger sisters, and I went to live with our two oldest sisters who acquired an extra room at an apartment house so we could join. My brother Bill went to live with our father on Larimer Street. Our oldest sisters had left camp in 1943 and worked at schools and went to Barnes Business College while our father paid their tuition. Our father had left camp before them to cut trees in Wyoming but eventually found it too cold and went to Denver and became a cook. Our sisters already had jobs in an office long before we left camp.

- May Murakami, Community Curator. May lived with her family at block 7H at Amache.

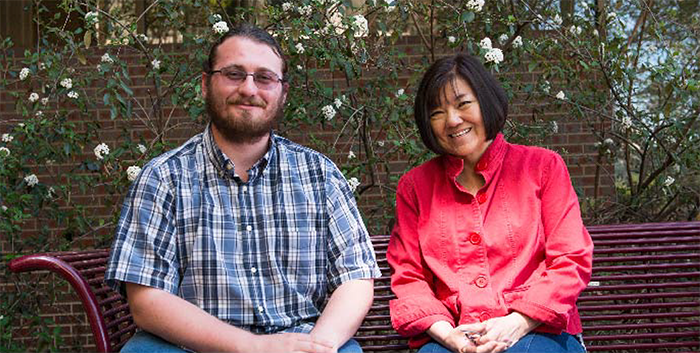

Left: May Murakami, Community Curator. Right: Todd Savolt, DU Student Curator.

-

Baseball

Baseball

Dimensional lumber, largest fragment 1.38" long. Found in Block 12H. How did archaeologists figure out these pieces of wood were part of the backstop of a baseball diamond? Archaeologists use a variety of methods to determine how people used objects in the past. The researchers at Amache used excavation, oral history, and historic photographs to shed light on the story of these pieces of wood.

In 2014, an archaeology team excavated block 12H of Amache. They uncovered several planks of cedar lumber that intrigued them because cedar was not available at the camp. A man who had lived at Amache later visited the site and described his memories about playing baseball in the camp. He pointed at the excavation site and said, "that is where we played baseball." Along with his oral history, the team examined historic photographs and noted a wooden wall in that same location, another line of evidence to interpret this as a baseball backstop.

- Mason Seymore, DU Student Curator

Baseball backstops adjacent to 12H and 12K bath houses. Courtesy of Helen Yagi Sekikawa.

Portions of backstop revealed in the 12H excavation. Courtesy of the DU Amache Project. Personal Reflection

Playing, watching and supporting baseball behind barbed wire brought a sense of normalcy... despite the harsh conditions of desert life and unconstitutional incarceration. - Nisei Baseball Research Project

WH-A-A-A-C-K!!! That sound resounding through an internment camp is a fascinating but little known story.

Japanese passion for baseball began in 1867 when American professor Horace Wilson baseball introduced the sport as a means to modernize the Japanese education system. When Japanese immigrants arrived in the U.S., they brought their love of the game with them. In 1903, the organized sport of Japanese American baseball began in San Francisco. In the following decade, immigrant Issei, who had learned the game in Japan, formed teams in California, Colorado, Washington, and Wyoming.

The popularity of baseball grew and by 1942 there were many league and semi-pro baseball players among the incarcerated Japanese Americans. Under their leadership, organized baseball went to assembly centers and then to internment camps, where they built diamonds and established male and female leagues. Internees were resourceful in finding materials for the game—moms made uniforms from mattress covers!

A tense moment in the Amache-Powers Country All-Star baseball game, Sunday September 12, 1943. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Baseball teams at Amache, Gila River, Poston, and Heart Mountain traveled to other internment camps to compete. The War Relocation Authority supported these teams because baseball conveyed a greater acceptance of American culture.

Among the members of the Amache baseball team was Harry Ishikawa, grandfather of current San Francisco Giant, Travis Ishikawa. Did his baseball roots begin at Amache?

- Millie Morimoto King, Sansei (third generation Japanese American). Incarcerated at Rohwer.

Kenichi Zenimura

Kenichi Zenimura is remembered as the Father of Japanese American Baseball. He played all nine positions well. As coach and manager he constantly led his teams to victory. On October 29, 1927, Zenimura's team, the Central Valley Fresno Nisei, beat Babe Ruth's all-stars 13-3. Zenimura was an international ambassador and he negotiated Babe Ruth's visit to Japan in 1934.

Zenimura baseball card. Courtesy of Bill Staples. Zenimura loved baseball. He founded the Nisei Baseball League throughout California in the early 1920s. At the Fresno Assembly Center he built a baseball field. In 1943 he and his sons built the Zenimura Field in Butte Camp at Gila River. The War Relocation Authority regarded the Zenimura Field as the finest of all the camp baseball diamonds. It was the only baseball field with grass, bleachers, backstop, dugouts, and castor trees for the outfield fence. Zenimura redirected water from the laundry room to water the grass on the field.

Games at Zenimura Field could draw up to 6,000 spectators. Zenimura organized thirty-two teams and three leagues at Gila River. He raised traveling funds by gate collections and selected box seats, collecting donations in coffee cans at third base and behind the backstop. The Issei love for baseball and gambling led to a lot of betting on games. Zenimura's passion and vision for baseball was contagious prior to, and during the war. Baseball at camps empowered the imprisoned with a sense of pride and hope.

- Cassidy King and James Knoblauch, Community Curators, Gosei (fifth generation Japanese American). Cassidy and James' grandmother and great-grandparents were incarcerated at Rohwer.

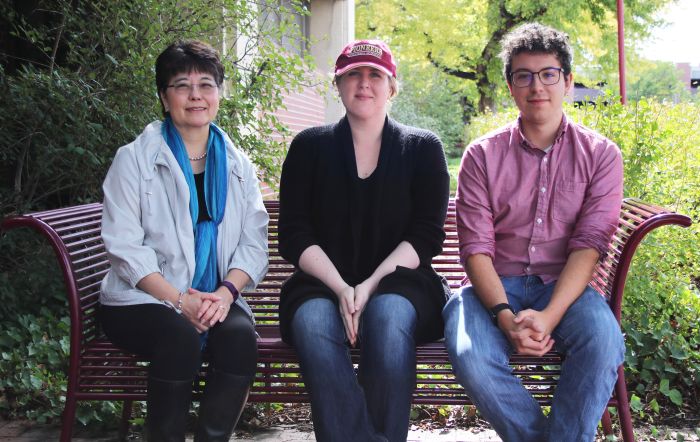

Left to Right: Millie Morimoto King, Community Curator. Cassidy King, Community Curator. James Knoblauch, Community Curator. Mason Seymore, DU Student Curator.

-

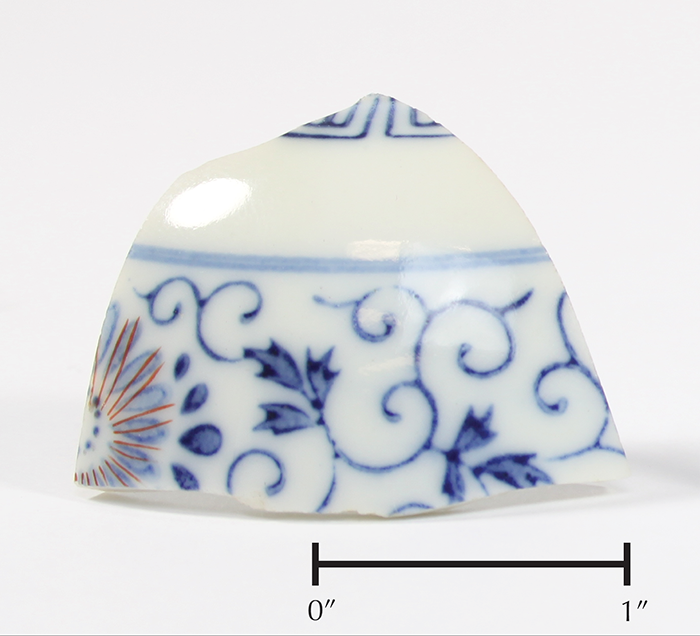

Bowl Sherds

Bowl Sherds

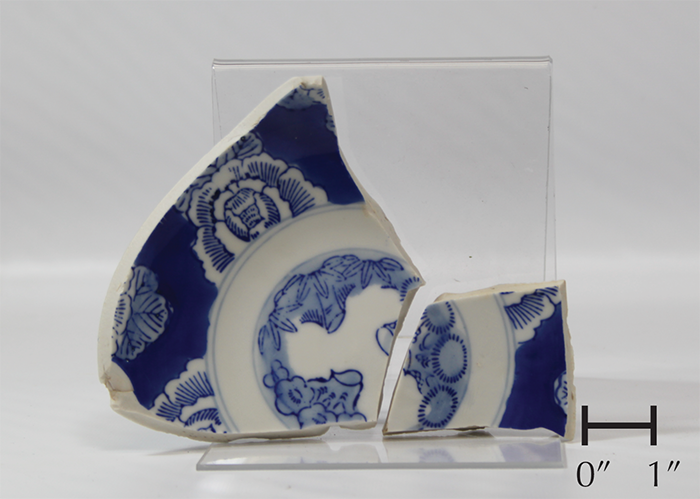

Porcelain, 6.4" wide. Found near Block 9L. These sherds of porcelain were once part of a large, ornate bowl belonging to a family at Amache. The thickness of the sherds suggests this piece would have been large and heavy, making it difficult to transport safely. It must have had great emotional value for a family to bring it to Amache.

The central motif of pine, bamboo, and plum trees (shochikubai—松竹梅) makes this serving dish especially appropriate to use for an auspicious occasion. The sherds were found in a dump site near the exit of the barracks, suggesting the piece was likely kept safe until the end of the family's time at Amache.

- Trevor Gilbert-Mayes, DU Student Curator

The Three Friends of Winter (Shochik Ibai - 松竹梅)

From Left to Right: Matsu (pine) represents longevity. Ume (plum) represents pure spirit. Take (bamboo) represents flexibility. Personal Reflection

The pieces of this bowl bring me only questions.

Mom, was this your bowl?

Since you were limited to how much you could take, why did you choose this over so many other possessions?

Did your mother or grandmother pass it down to you?

Was it one of your prized possessions or your only prized possession?

Was it something that you had hoped to pass on to your children?

Was it something that you thought would help preserve your Japanese heritage?

Did Dad tell you that you were being foolish to take such a thing?

How did you get it from your house to the race track and then to the train that took you to a place that you knew nothing about?

Did you wrap it in a furoshiki?

Were you able to use it while at Amache?

Did you ever have a chance to serve traditional Japanese foods in it?

Did you ever have a chance to share food in it with friends while in "camp?"

Were you heartbroken when it broke?

I didn't know to ask these questions while you were alive. And you didn't share with me those stories. Broken and I have no answers. However, I am proud that you and Dad picked up the pieces of your life and started over again.- Ann Naome Yoshihara-Murphy, Community Curators, Sansei (third generation Japanese American). Grandfather, parents and siblings incarcerated at Amache

Furoshiki by Ann Yoshihara-Murphy. Photo by DU. Internees brought valuable items to camp in a furoshiki, traditional Japanese wrapping cloth used to transport clothes, gifts, food or other items. In Japan, before the modern age, a furoshiki was used to wrap your clothes in when going to a public bath or furo. Isn't this a lovely way to take food to a pot luck? More eco-friendly than a plastic bag.

Left: Trevor Gilbert-Mayes, DU Student Curator. Right: Ann Yoshihara-Murphy, Community Curator.

-

Cracker Jack

Cracker Jack

Lead and Tin Alloy, .86" long. Found in Block 7K. Cracker Jack toys are an iconic and nostalgic phenomenon spanning generations. Archaeologists found this fragment of a metal toy in block 7K at Amache. Student research into the object's design confirms that this is a Cracker Jack toy. X-Ray analysis shows that this toy is crafted from a mixture of lead and tin alloys, a combination that was only used between 1939 and 1941 during the tension-filled years preceding the United States' entry into World War II. This fragment was found in front of the Yokoyama family's barrack in Amache. Since there were few other families living in this section of the block, it is very likely that the toy belonged to someone in that household and was probably brought from home to Amache.

- Megan DeBard, Student Curator

Personal Reflection

Cracker Jack Toy Packet. Courtesy of Dennis Miyashiro. This fragment of a Cracker Jack toy immediately conjures the memory for generations of kids, of opening a box of the candy-coated peanuts and caramel corn and shaking out that prized pouch to get to the toy. Opening the pouch, you might be delighted or disappointed with the toy, depending on whether it's something you wanted or not.

Reproduction of 1930s era packaging. Courtesy of Jason Liebig This rider on a horse was probably one of the cool toys. It's easy to imagine the young boy Yoshio of the Yokoyama family, in front of whose door the fragment was found, kneeling in the dirt of Amache and playing with the rider. Maybe it was part of a bunch of riders, or maybe it was a lone cowboy.

The Cracker Jack was probably purchased not long before the family was sent to the concentration camp. Yoshio may have clutched it in his hand, or kept it in his pocket for safe keeping, during the long train ride from Los Angeles, where his family had lived before the war. Playing with the toy was a way to make life as normal as possible in the camp.

Somewhere along the line, it got lost, or dropped, or broken and discarded.

This tiny fragment of a mass-produced toy is a key to an entire life. Imagine playing with it at Amache, and you're transported to that time and place, and can feel the injustice of sending a boy to such a place to treasure a Cracker Jack toy as a prized possession.

- Gil Asakawa, Sansei (third generation Japanese American, Community Curator. Author of Being Japanese American.

Left: Gil Asakawa, Community Curator. Right: Megan DeBard, DU Student Curator.

-

Dog Figurine

Dog Figurine

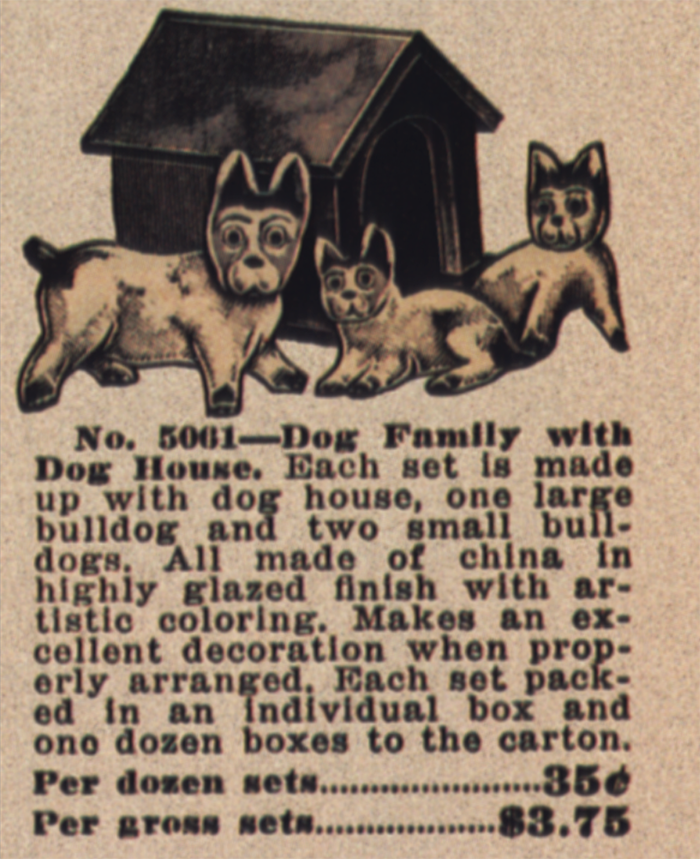

Porcelain, 2" long. Found in Block 9L. Archaeologists found this porcelain bulldog on the edges of camp among a trash pile. Sold as part of a set, the figure was meant to be enjoyed for its aesthetic values. The JAPAN export stamp on the back tells us that it was imported before the U.S. cut trade relations with Japan during the war.

Found with its legs broken and paint worn off, the small dog went through much wear after its move to camp, suggesting it was used for more than just display. Bulldogs are not native to Japan but they are very popular there. Today, French bulldogs are among the top ten favorite dog breeds in Japan.

- Cassandra Cortright, DU Student Curator

1930s catalog illustration of dog family set made in Japan. The figurine on the left is similar to the one recovered from Amache. Courtesy of Wholesale Premium Merchandise & Novelties catalogue. Personal Reflection

"The dog is mine!" That's what I said to Dr. Clark when asked to choose among the various objects for this exhibit. I chose this one because, very simply, I love dogs. I believe it was someone's memento of a beloved pet she (or he) had to leave behind—a small object of great significance that did not take up valuable space needed for essential items. More than that, we'll probably never know.

The Shitara family were among the lucky few who were reunited with their pets at Amache. A family snapshot captures Carlene Tanigoshi with her grandfather's dog, Queen. Courtesy of Carlene Tanigoshi Tinker. I live in an area where wildfires are a threat. Preparing for evacuation includes gathering the "3 Ps": papers, pictures, and pets. Papers, no problem. Pictures, we're covered. Pets, of course; my husband and I would not think of leaving without the two dogs and two cats who share our home and our lives. We'd just load it (and them) all up in our SUVs and drive off to safety, to return when we received the "all clear."

That's not the way it was for those forced to leave their homes in 1942. They took only what they could carry, not knowing when (or if) they would return. There are accounts and pictures of dogs with their families at Amache; but there are many more stories about families at Amache and other camps who had to leave their beloved pets behind, with heart-breaking consequences—Laddie who "died only a few weeks after we left Berkeley," Jimmie who starved himself to death after his family gave him to a friend, or Frisky who reunited with his family after three years.

How did this precious object end up dumped at Amache? How did it become so damaged? Thrown in grief after hearing the real pet had died? Accidentally stepped on during the rush to leave camp? We'll probably never know.

- Mary Ann Amemiya, Community Curator

Left: Mary Ann Amemiya, Community Curator. Right: Cassandra Cortright, DU Student Curator.

-

Geta

Geta

Likely carved from dimensional lumber, 8'' long. Found in Block 11F. It's hard to imagine people in America resorting to wearing sandals hand-carved from pieces of scrap lumber, isn't it? Yet resourceful Japanese Americans found themselves having to do exactly that while in internment camps. Many internees at Amache wore these handmade wooden shoes, and remnants of these sandals, called getas, were found at the camp. This geta is among the smaller of those recovered during research. Getas are traditional Japanese sandals made from wood and look like flip-flops.

They have a platform elevated by two "teeth" and a fabric thong threaded through the toe. Traditionally worn with kimonos, getas elevate the wearer to protect their feet and clothing from rain, snow, mud, and dirt. The handmade getas at Amache were functional, helping internees deal with the camp's harsh conditions. But they were also culturally important, worn during traditional activities such as Obon, a Buddhist festival celebrated yearly at Amache.

- Emily Barriball and Nick Beeson, DU Student Curators

Historic photograph from Amache scrapbook of girls wearing getas with kimonos for Obon. Courtesy of Helen Yagi Sekikawa. Personal Reflection

"Assigned to 11G, 11D. dirty brick floors. Ants and other insects keep coming up. A sand storm greeted us upon arriving at camp."

9/21/42 Journal entry from Yoneko Uyemura, age 21Seeing the wooden geta brought this entry from my mother's journal to mind. Living in Amache, meant dirty floors and often muddy passageways. I'm sure footwear that could elevate, if only for an extra inch or two, would have been welcome–especially for that trip to the latrines. I imagine that this geta belonged to a small person, perhaps even my grandmother who stood only 4'8" tall. My mother and other incarcerated family members would often recall how difficult life in camp was for the Issei and elderly. The lumber, out of which this geta appears to have been carved, also brought to mind a small table in our home in Trinidad, Colorado.

I later learned that my dad and uncle built it from scraps of discarded lumber from the hastily built barracks. My mother also kept a beautiful bird pin carved as a gift in camp. Wood provided a welcome avenue for resourcefulness, creativity, and a break from the monotony of camp life. Like many Nisei, my parents were such remarkable individuals, but very reluctant to speak of their Amache experiences. These objects provide even deeper insight about the internees, all of whom deserve our continued respect, admiration, and most importantly, remembrance.

- Janice Reiko Ogawa, Community Curator, Sansei (third generation Japanese American), grandparents, parents, aunts, and uncles incarcerated at Amache

Left: Janice Reiko Ogawa, Community Curator. Center: Emily Barriball, DU Student Curator. Right: Nick Beeson, DU Student Curator.

-

Grater

Grater

Tin can lid, 5'' long. Found in Block 9G. An internee at Amache fashioned this grater from the lid of a large tin can with the sharp edges folded over. The craftsmanship is impressive considering the limited resources in camp. Notice the size and shape of the holes. What could they have used to make the smaller, square holes? The clandestine cook could have used the large hole on the end to safely hang this sharp item on the wall.

The War Relocation Authority banned personal cooking in barracks, yet it was an important way for individuals to maintain their cultural roots. Internees often fabricated their own cooking implements from materials available in their respective camps. This grater is just one of the many clever uses of items to infuse the flavors of home into an institutional diet.

- Mackenzie Mantsch, DU Student Curator

Erin Yoshimura, Community Curator Personal Reflection

This artifact, thought to be a home-made grater, caught my eye because it provides a snapshot into camp life. Although it would be suitable for ginger, it seems more likely made to use with daikon (Japanese radish) because shoga (ginger root) grows in hot climates. Farmers incarcerated at Amache grew many crops in the fields associated with the camp, including daikon. A versatile vegetable, daikon can be cooked, pickled and eaten raw but when it's grated or what we call oroshi, its flavor comes alive. The sharp edges of this homemade grater are just the type needed to grate daikon into a pulverized texture. Daikon oroshi is a condiment and adding a little shoyu (soy sauce) and eating it with grilled fish or steak enhances the flavor. Adding daikon oroshi to ponzu or tempura dipping sauces is a must at our table. Perhaps the ability to make daikon oroshi could have served a dual purpose for whoever crafted this item. Not only would it enhance the flavor of poor quality food, it could provide some familiarity and culinary comfort in an unbearable time in their lives. Both shoga and daikon are staples in our refrigerator and I often reach for my special Japanese graters without a second thought. Would I risk working with a sharp can lid to fashion my own grater? Yes!

- Erin Yoshimura, Community Curator, Yonsei (fourth generation Japanese American), parents, grandparents, and great grandparents were incarcerated in Tule Lake and Rohwer

Daikon growing in the fields associated with Amache. Photograph by Joseph McClelland. Courtesy of the Amache Preservation Society.

Daikon oroshi. Photograph by Gil Asakawa.

Left: Kevin Blunt, DU Student Curator. Right: Mackenzie Mantsch, DU Student Curator.

-

Obsidian

Obsidian

Stone, 4'' wide. Found in Block 7H. Imagine you have one week to gather the things that are most important to you and relocate to an internment camp. What would you bring? Archaeologists have revealed that the answer to this question may surprise you. A type of natural glass created by volcanic action, obsidians carry trace elements specific to their source. Behind one of the barracks at Amache, archaeologists found this piece of obsidian that sources back to Glass Mountain, Siskiyou County, California.

This piece is thought to have functioned as a part of an extensive garden that wrapped all the way around the outside of the barrack. You may think raw obsidian looks pretty unremarkable, but once its outer covering is removed, it becomes a beautiful piece of shiny black stone. It took a great deal of skill and time to create this worked obsidian and must have been valued by its collector.

- Missy O 'Doherty, DU Student Curator

Personal Reflection

Amache Gardening Evolves

One of the first tasks of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was to find concentration camp sites for the over 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry removed from the west coast. So that farming programs at the camps could be successful, the agency chose sites based on existing irrigation projects or agricultural potential. Privately owned farms and ranches were purchased or condemned to establish Amache. The WRA purchased water rights from Lamar, Marvel, and the XY canals, and used the Arkansas River, 2.5 miles to the north of the central camp area, to water some fields. At its height, Amache agriculture was successful enough to supply Amache as well as other WRA camps.

With water available, the Amache internees transformed a harsh environment to one that reflected their culture by planting trees, constructing ponds, and growing victory gardens. Entryway gardens for individual barrack apartments helped break up the institutional monotony. The gardens demonstrate how internees progressed from an attitude of acceptance and resignation – 'it cannot be helped' (shikata ga nai)—to one that showed "perseverance and fortitude," or gaman. Thomas Shigekuni, whose family lived in Block 12G at Amache, remembers planting trees at the camp with his brother Henry. Before the war, their family was in the nursery business in Los Angeles. They were familiar with how the Chinese Elm goes dormant in the winter thus helping it withstand harsh winters. Henry was granted permission to go to Lamar to purchase Chinese Elms for $.50 each. He bought enough 6' trees for his family and other residents of his block.

He also purchased peat moss to ensure the successful transplanting that resulted in most of the trees still standing today. Through oral histories, we know some plants were purchased in nearby towns. Excavations also reveal that Amache's gardeners transplanted local vegetation like yucca, asters, wildflowers, and purslane into their gardens. Other plants were grown from seeds brought with internees or purchased from mail order catalogues. Stones, a common feature of traditional Japanese gardens, added pleasing, aesthetic and cultural elements. Many of the stones archaeologist have found in Amache's gardens were gathered locally, but others, like this one, were brought to camp from some distance. The rock in this garden, could be a keepsake of a meaningful event prior to incarceration and a symbol of hope for the future.

- Millie Kenko Morimoto King, Sansei (third generation Japanese American), incarcerated at Rohwer with parents, aunts and uncles incarcerated at Tule Lake

Worked Obsidian: An Amache Mystery

Through analysis of trace elements, archaeologists know this stone originally came from an extinct volcano high in the Sierra Mountains of California, Glass Mountain. Most of the residents of Block 7H where this stone was found, lived in California, but about 300 miles south. Glass Mountain is about 30 miles from Tule Lake, another WRA camp. Beginning in the Fall of 1943, hundreds of incarcerees from Tule Lake were transferred to Amache. Just like the Amache internees, they may have picked up beautiful stones such as this on their excursions away from the California camp.

How did this object make its way to Amache? Ainsley Hana King and Peter Austin Knoblauch, whose family were interned at Rohwer, Manzanar, and Tule Lake, wrote these books presenting two different scenarios to help us imagine its journey.

Elementary school children landscaping outside the school barrack. Older children created the garden designs. Photograph by Joseph McClelland, Courtesy of the National Archives, NARA_539398.

Improvements in common areas saw trees planted/transplanted between barracks and around mess halls, construction of ponds, several vegetable Victory Gardens, and more decorative entryway gardens. Photograph by Joseph McClelland. Courtesy of the Amache Preservation Society.

Left: Peter Austin Knoblauch, Community Curator. Left center: Millie Kenko Morimoto King, Community Curator. Right center: Missy O'Doherty, DU Student Curator. Right: Ainsley Hana King, Community Curator.

-

Pitcher

Pitcher

Enameled metal, 8.5'' wide. Found in Block 9G. Archaeologists excavated this pitcher in an undeveloped block towards the middle of the camp. Made of pressed metal, the pitcher has an enamel coating making it water resistant. Such cheap wares were typical of those supplied by the War Relocation Authority for use in mess halls. Due to the distance between this pitcher's location and any mess hall, it is likely that it was removed from a mess hall for personal use.

Individual barracks at Amache were not plumbed, so access to water was limited to the laundry room and one outside spigot. This made staying hydrated and fetching water a time-consuming task for most. The pitcher served as a portable water station, lightening the load for the individual or family that used it.

- Cole Hoholik and Will Friedman, DU Student Curators

Historic photo of Amache mess hall. Similar pitcher on table in foreground. Photograph by Jack Muro. Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum. Personal Reflection

This enamelware pitcher in itself is not special—one of many, unremarkable and cheap. They were among the wares supplied by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), who oversaw the internment of Japanese Americans. It belies their disregard and lack of readiness to adequately provide for the unjustly incarcerated, whom they claimed to be protecting. Similar pitchers appear in photographs taken at Amache by internee Jack Muro. Muro was imprisoned at Amache, and despite cameras being contraband, managed to take and develop a significant portfolio of photographs. He took it upon himself to dig out and build a darkroom, and I am grateful for his efforts which have allowed me and others to more fully understand this history. Many of the photos that emerged from the various concentration camps were commissioned by the WRA and used for propaganda.

They remain an inaccurate portrayal of what daily life actually looked like, while those taken by Muro and other internees provide real insight on the perspective of Japanese Americans at the time. Most of my family was interned at Tule Lake in California, while my Issei great grandfather was held separately at a POW camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico. Before being incarcerated during WWII, he had been an avid photographer (and vegetable farmer by trade) in Kent, Washington; but I lack a visual understanding during their years of internment. As an artist, I seek to disseminate this lost history, and photographs such as Jack's are indispensable to that process. They remain evident of radical perseverance in spite of overt racism and oppression. Much like this commonplace pitcher, they help to complete an incredibly important history now forgotten.

- Sarah Mae Fukami, Community Curator, Yonsei (fourth generation Japanese American), Hapa (partial Asian decent), family incarcerated at Tule Lake and Lordsburg, NM

Left: Cole Hoholic, DU Student Curator. Center: Sarah Mae Fukami, Community Curator. Right: Will Friedman, DU Student Curator.

-

Plane

Plane

Intact example of the Mystery Plane from Wyandotte Toy Company. Collectors date this plane to the late 1930s. Analysis of the toy's material confirms this date. Steel toys were not made during the war due to metal rationing. Courtesy of Ebay. When Amache families left their homes, they packed only their most precious items. Despite luggage limitations, they gave some of that valuable space to toys for their children. Archaeologists found this broken toy airplane in the common areas of a barracks block. This toy was produced in the late 1930's by Wyandotte Toy Company.

This was a likely a beloved toy, already years old when it arrived at Amache with its owner. The airplane had hooked back wings, windows, and no guns attached signifying that it was a passenger plane. The plane would have originally had wheels made of rubber or wood. What games can you imagine were played with the plane? Adventures set in the future? Travel outside of camp? Covert spy operations? To think of these games provides insight into the lives of children in Amache.

- Avery Niemann and Colin Orlowski, DU Student Curators

Intact example of the Mystery Plane from Wyandotte Toy Company. Collectors date this plane to the late 1930s. Analysis of the toy's material confirms this date. Steel toys were not made during the war due to metal rationing. Courtesy of Ebay. Personal Reflection

In the two decades between the World Wars, the American toy industry reflected the innovations of flight that were developed during WWI and the early years of commercial air travel. One company, Wyandotte Toys, whose original name was All Metal Products Co., manufactured all manner of toys from its start in 1921 to its closing in 1957. Although the company became popular with a variety of guns, during the Depression it began stamping out toy cars, baby carriages and airplanes. Many of its toy planes were standard copies of WWI warplanes or typical planes, but one model sold during the late 1930s was different. The Mystery Plane embraced the science fiction hits of the day, Buck Rogers (a comic strip first published in 1929) and Flash Gordon (whose comic strip debuted in 1934).

These pre-space age heroes sparked the imagination of Americans including children–especially young boys. During times of economic hardship, it must have been a thrill to follow the adventures of cool guys in a far-off, future time and place. And Wyandotte's Mystery Plane played to that fantasy – it was a normal airplane with propellers, but its wings were extended backwards like a space-rocket design. It appeared aerodynamic in ways that looked forward into the future, not the past. It was all about speed and hope. That sense of hope still surrounds the rusted, broken Mystery Plane that was found at Amache, in an open space between a barrack and mess hall. It begs us to imagine a young child, probably a boy, playing with this utterly cool-looking plane during his family's incarceration.

One of the wings may have broken from rough play, or maybe it was dropped and remained unnoticed and the wing broke when someone stepped on it. Then the red paint oxidized, and steel rusted over the decades, the now-lonely toy waiting to be discovered. The plane, which is more mysterious today than it was 70 years ago, must have symbolized hope for the child who played with it, holding it against the endless blue sky of Southeast Colorado: Hope for the future, and hope of freedom for the close to 10,000 people imprisoned in Amache.

- Gil Asakawa, Community Curator, Sansei (third generation Japanese American), author of Being Japanese American

Left: Avery Niemann, DU Student Curator. Center: Gil Asakawa, Community Curator. Right: Colin Orlowski, DU Student Curator.

-

Porcelain

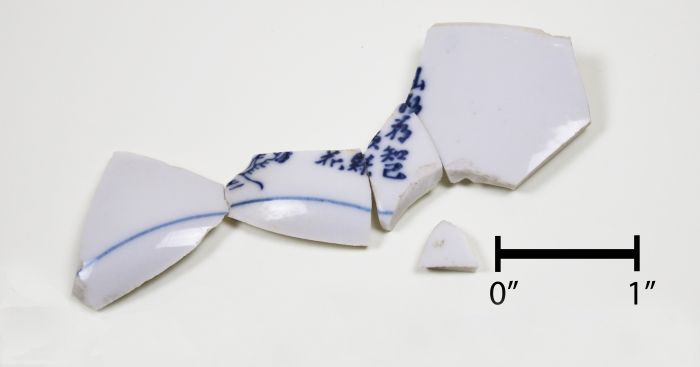

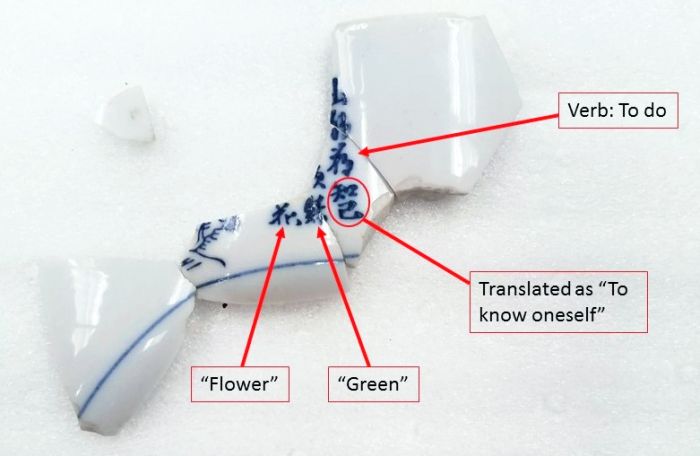

Ceramic Sherds with Chinese Characters

Porcelain, largest fragment 1'' wide. Found in Block 9G. The Chinese characters on these ceramic fragments may be part of a poem of classic Chinese literature. Such decoration was common for mass-produced dishes imported to the U.S from Asia. Because the U.S. began heavily restricting the importation of Asian goods in the 1920's, someone possibly purchased this ceramic before then. Popular among immigrant communities, imported dishes were used to serve traditional foods, reinforcing strong ties to their cultural heritage.

Using the arc of the ceramic fragment's lip, one can estimate the intact vessel was 11 cm in diameter. The size and cylindrical shape suggest it was likely a soup bowl. Soups, such as miso, are integral to traditional Japanese cuisine. Internees could buy ingredients for such soups in the fish market in neighboring Granada. Internees at Amache prepared foods of their Japanese heritage as a means of preserving their cultural identity and retaining a sense of autonomy during the uncertainty of internment.

- Meg Bailey, DU Student Curator

Photograph of bowl fragments noting translated characters. Graphic by Brianna Dalessandro. Personal Reflection

Archaeologists have discovered many broken pieces of ceramics associated with traditional Japanese food and drink at Amache. These fragments reveal how people appreciated having familiar tableware for serving Japanese cuisine while their lives were disrupted during internment. Varying in size and shape, specialized ceramics were used to serve tea, sake, rice, and soup. Some families took Japanese porcelains with them when they were interned in 1942; others had things shipped to them later. By 1943, Japanese green tea could be purchased from a nearby fish market in Granada, and tea was included among the gift goods sent to internment camps by the Japan Red Cross. Fragments of sake cups, flasks, bottles, and jugs were recovered at Amache, where internees brewed their own sake or purchased it from a local drugstore.

Soy sauce, noodles, rice, and other foodstuff were available for fixing favorite dishes. Made from soybean, tofu and miso could be used to prepare soups like suimono and misoshiru. Nori, an edible seaweed, was a rare commodity; hot dogs and canned SPAM® became common substitutes for fresh meat and fish. In 1942, my mother, her parents, and her younger sister were displaced from California to an internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, where I was born. Since my family returned to Los Angeles before I was a year old, I have no memory of that experience. However, my aunt recalls that they took a vintage teapot and teacups with them and says that she will bequeath these ceramics to me. She recounts that my mother gave her a canister of nori, used to make sushi rolls and rice balls (musubi, onigiri). The dried seaweed was too precious to eat so she still has it saved in its original tin container, seal unbroken.

- Ronald Yetsuo Otsuka, Community Curator, Sansei (third generation Japanese American), born at Rohwer, interned with mother, maternal grandparents and aunt, paternal grandparents and aunt interned at Poston, father in the 442nd Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army

Left: Meg Bailey, DU Student Curator. Right: Ronald Otsuka, Community Curator.

-

Soda Bottle

Soda Bottle

Clear glass, 2'' wide. Found in Block 11K. Imagine unwinding at the end of the day with an ice-cold soda pop. Although most people take this commonplace indulgence for granted, this was not the case for the people in the Amache incarceration camp. A simple bottle of soda represented a connection to life outside the camp. Soda was available for purchase either in nearby Granada or the cooperative store located in the camp. This particular bottle was manufactured in Lamar, 18 miles west of Amache, and shows significant wear most likely from reuse. This wear and tear reveals that soda offered not only the hedonic value of being a tasty treat to those in the camps, but also utilitarian value as an extra container that could either be refilled or reused in day-to-day life. To the Amache internees, soda was a simple luxury to make life in the camp a little sweeter.

- Marie Ferdinand and TJ Norris, DU Student Curators

The Amache cooperative canteen gave the internees the opportunity to purchase items, such as soda, which many Americans took for granted in everyday life outside the camp. Photograph by Tom Parker, War Relocation Authority. Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. Personal Reflection

I was born at the end of World War II. Since my parents and family lived in Colorado, my relatives were not incarcerated in any of the camps. This soda bottle from Amache reminds me of helping my father and uncles on the farm. At seven, I was too young to work alone and had no real responsibilities. I thought it was fun because I was able to drive the pick-up or tractor in the fields like the adults. During this time, I got to go with them to the town cafe and would get a soda drink and listen to the men talking. The soda drink was a treat for me on a hot, sweaty summer day and I enjoyed the time of feeling connected with my family. When I was eight or nine, the work I was responsible for shifted. I began working alone from morning to sundown with no breaks for sodas. I think this shift reflects a Japanese cultural value, that of taking responsibility and working hard. Just as I found enjoyment and family connections around the drinking of soda, I hope that the soda was a way of maintaining some semblance of family life in the harsh conditions of the camp.

- Alvin 'Seichi' Otsuka, Community Curator, Sansei (third generation Japanese American)

Internalized Oppression

By Alvin 'Seichi' OtsukaJapanese living outside of the exclusion zone were spared overt imprisonment. However, the covert imprisonment has left psychological scars that have been difficult to understand and sort out. Japanese culture has instilled values that I believe play into the internalized oppression that creates the covert imprisonment. Japanese culture instills the values of respect for others, keeping quiet, and maintaining an invisible presence when interacting with others. I believe this was overly emphasized by my parents due to the incarceration threat during World War II, and carried on after the war. Post-World War II, the prejudices that led to the executive order that incarcerated 120,000 Japanese American Citizens and first-generation Japanese, continued the internalized oppression in the subsequent generation. I learned the lesson of internalized oppression so well, that it took years to understand the racism that existed around me and to me until the past 10-15 years of my life. Gaining this understanding of oppression has allowed me to calm the internal turmoil and reach a peace within myself.

Left: Marie Ferdinand, DU Student Curator. Center: Alvin 'Seichi' Otsuka, Community Curator. Right: TJ Norris, DU Student Curator.

-

Stone

Garden Stepping Stone

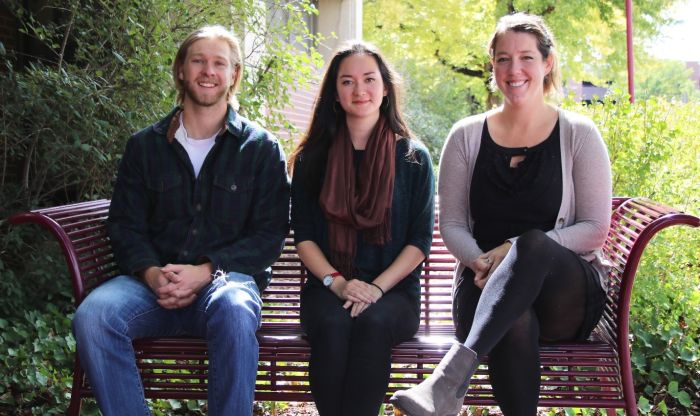

Concrete, 8'' wide. Found in Block 11H. This is one of three stepping stones recovered from a garden discovered in the 11H barracks block. The two unmarried men who shared this barrack were former professional gardeners and researchers believe that this garden was created to serve as both an ornamental and functional garden. Judging by the position of the stone to the doorway as well as other features of the garden, it appears as though the garden was designed to promote mindfulness as well as produce edible plant life. Notice the three rough and one smooth edge of this concrete stepping stone. This smoother edge possibly indicates it was broken off of the base of the barrack foundation by a camp resident. These gardeners were not alone in repurposing materials in creative ways at Amache. Internees reclaimed personal independence within camp by both differentiating living spaces as well as maintaining cultural ties, often through their own gardens.

- Melanie Leiner and Dain Priday, DU Student Curators

View to 11H garden wall from barrack entrance showing original location of the garden stepping stone. Additional stones uncovered during excavation reveal a path curving around the wall. Courtesy of DU Amache Project. Personal Reflection

Left: Dain Priday, DU Student Curator. Center: Holly Kawase Kirkman, Community Curator. Right: Melanie Leiner, DU Student Curator.

-

Syrup Tin

Syrup Tin

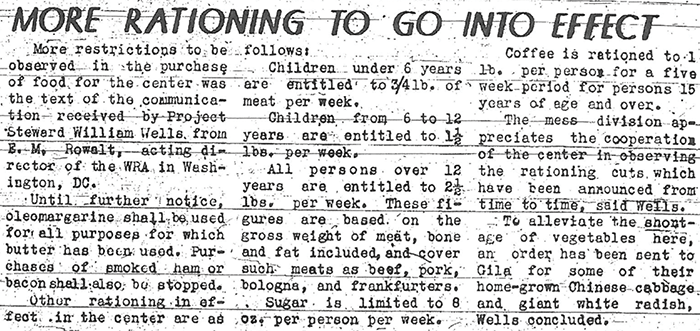

Metal, 6" wide. Found in Block 8F. The barely visible writing and distinctive shape indicate this is a Log Cabin syrup tin, dating to World War II. During the war, many items, including sugar, were rationed because of shortages. Syrup was an exception and could have been a way to bend the rationing rules.

Archaeologists found this tin in the 8F block of Amache between a barrack and the road, very close to the mess hall. Did a young child have a sweet tooth and bring the tin to the barracks? Did someone repurpose it to use as a watering can in a backyard garden?

- Kelley Rankins, DU Student Curator

The February 4, 1943 edition of the camp newspaper announced that each Amache internee was now restricted to 8 ounces of sugar a week. Courtesy of History Colorado.

Log Cabin Syrup Tin, circa 1940s. Courtesy of Patrick Dirden. Personal Reflection

This syrup tin represents an aspect of the changing diet reinforced by unknowing American purchasers of food stuffs for the camps. The common Japanese breakfast was a bowl of cooked rice with hot tea over it, much like cold cereal topped with milk. You could add pickled vegetables and, occasionally, some protein. Foods requiring sugar were not common. Mochi, a sweet treat made of pounded pulverized rice, does not require sugar in the mochi itself.

Chazuke, a traditional Japanese breakfast made from pouring hot tea over cooked rice. Courtesy of Jaimie M Lewis. The sauce to dip it in is made with a sweetener (sugar or syrup possibly) and soy sauce. This tin might also reflect the Japanese propensity for keeping things for future use. My mother saved plastic containers and even washed plastic bags to reuse. The size of the tin might make it useful as a water container as metal was rationed and many plastics were not yet available.

The stopper in the metal neck had not been removed, making the opening to the tin difficult. Being found so close to the road and mess hall, along with the stopper not being removed, might indicate it was refuse that had fallen from garbage being taken out. If it had been on the road for any length of time, someone would have gathered it for reuse or a toy or just to keep the area neat and clean. A child could have wanted the tin for a toy, but with the sharp edged stopper still in place a parent might object.

How would you use this tin?

- Linda Takahashi Rodriquez, Community Curator

Left: Linda Takahashi Rodriguez, Community Curator. Right: Kelley Rankins, DU Student Curator.

-

Tea Pot Lid

Tea Pot Lid Fragment

Porcelain, 1.75" wide. Found in Block 8F. This item's size and shape indicate it is a fragment from the lid of a porcelain teapot or porcelain jar. The intact lid would have been about 2" in diameter. Archaeologists found the fragment in the dirt between the barracks and the Mess Hall. Based on its texture and Chinese-inspired designs, common motifs on Japanese ceramics, it was most likely made in Japan and brought to Amache by one of the families there.

Tea drinking and tea ceremonies were unifying events in Japanese culture and a tradition that continued at Amache. A family's heirlooms were respected and taken care of, especially dishware. The presence of this teapot at Amache indicates the owners' strong attachment to their heritage. The teapot and its meaning brought a sense of cultural normalcy to a new, disconcerting home.

- Olivia van den Berg, DU Student Curator

Tea grown on the Amache form being dried in the outdoor shed for use in the mess halls. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Personal Reflection

I chose this object because it seems familiar to me. Growing up, we celebrated O-shogatsu (New Year's Day) with osechi-ryori, many special foods to bring us luck and prosperity in the New Year. Obaachan (great-grandmother) and my grandmother would cook and prepare special foods for many days and that's when the special sara (plates) would come out. A dozen large, beautifully painted platters and bowls filled with savory delicacies only served once a year. I remember sitting at the table, tracing the intricate swirls and geometric patterns with my eyes.

Osechi-ryori traditional Japanese foods eaten on the Near Year. Courtesy of Dave Nakayama, www.flickr.com. Amazing how a small fragment of a teapot brings back wonderful memories of family and food.

When I held this object in my hand, I started to wonder about the family and how this teapot must have been very important to them to bring it to camp if you could only bring what you could carry. If they're like my family, they took measures to keep the teapot from breaking. I imagine this teapot must have provided some comfort and helped them remember life on the other side of the barbed-wire fence, a time when freedom was as natural as breathing.

How did the teapot get broken? Why was there only one small fragment found and where is the rest of it?

The fragment is in excellent condition as if it was recently broken and not buried in the desolate earth.

Was the family sad to lose their treasured belonging? Or, was it easy to leave behind the broken pieces along with the trauma and shame of being yanked from their homes simply because they were Japanese?

Little did they know that the trauma and shame would forever leave an indelible mark in their family history. Little did they know that the sherd of teapot was a piece of their broken spirit and, while you can bury it for a while, it will resurface someday.

- Erin Yoshimura Yonsei, Community Curator (fourth generation Japanese American). Erin's parents, grandparents and great grandparents were incarcerated in Tule Lake and Rohwer.

Left: Erin Yoshimura, Community Curator. Right: Olivia van den Berg, DU Student Curator.

A traveling version of this exhibit is available at no cost to appropriate venues. For more information, please contact Dena Sedar dena.sedar@du.edu.