Graduate Students Tackle Health Communication in Malawi with Global WASH Project

By Ivey Bostrom, Second-Year MA in International & Intercultural Communication Student

This summer I had the incredible opportunity to evaluate a shallow wells program in Malawi, Africa. I was part of a faculty and student team from DU and Virginia Tech led by Dr. Renée Botta and Dr. Emily Vanhouweling of DU and Dr. Ralph Hall of Virginia Tech. Divided into three teams, we worked in the Northern, Central and Southern regions of Malawi. The program was a crucial part of WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene), a development effort working with the Marion Medical Mission (MMM), which has installed over 15,000 shallow wells over the past two decades in Malawi. Our objectives were to quality test the shallow well water and compare the data with similar communities who were waiting for construction of a shallow well in their village. We walked away with a lot more than data.

When we first arrived in the capital city of Lilongwe, we spent two days visiting the US Embassy. There, we would learn that Malawi is one of the least developed countries in Africa and has a severe need for water and sanitation services. Bordered by Mozambique, Zambia, and Tanzania, only 8% of Malawi has access to electricity, and many regions of the country experience frequent blackouts. Despite the lack of infrastructure and governmental aid, Malawi is known for being "the warm heart of Africa." As I would learn over the next three weeks, this statement could not be more accurate,.

After seven hours of travel by bus, including one break down and a luggage mishap, we arrived in beautiful Mzuzu, where the University of Mzuzu would be our home for the next week. At Mzuzu, or “’zuzu” as the students say, we took classes and trained for fieldwork alongside our Malawian counterparts who would become our colleagues, collaborators, and dear friends. Everyone had a role on each team, providing leadership in a focus group, key informant interview, or in a household survey team.

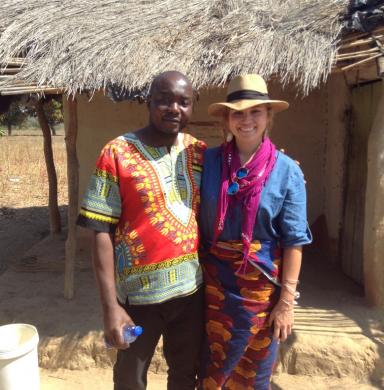

I was part of the household survey team with my partner Elton Chimwemwe Chavura. We traveled to five communities over the next 10 days to conduct around 60 household surveys. Each survey consisted of questions regarding water collection, daily life, and sanitation practices. I found that it is difficult to measure variables such as time in a community that doesn't value time the way Westerners do. For most people we surveyed, time does not equate to a number of hours, but is instead based on the sunrise and sunset.

The most difficult part of the survey involved asking people this question: "Have any children in your household died from water contamination?" As we traveled to the most rural and poorest communities, too often the answer was, "yes." Although we received technical training to test water samples and prepare for the field, field training can never prepare you for the emotional challenges that come along with this work.

A vivid memory of a woman I spoke with comes to mind. Sitting on a wet dirt floor saturated in chicken feces, Ateefah’s cloudy eyes looked into mine with despair and devastation. Her eyes cast downward, and then suddenly she looked up for a moment and said, “every one of my five children is gone … I have no one left.” I absorbed her profound sadness. My eyes immediately welled up and tears fell heavily onto the dirt floor of her home. As I walked away, Ateefah said, “I wish you would have come here to help when I was younger,” perhaps implying that her children might still be alive if someone had come to help. I could not take five steps before I broke down and cried for Ateefah, wishing too that someone would have come earlier.

Elton and I sat together afterward and discussed the severity of the crisis for communities without clean water, contemplating if there was anything we could do now to create a solution for cleaner water. There is no simple or fast solution when tackling water and sanitation in international development. One thing we learned from Dr. Renée Botta was that behavioral change comes first, and that is a slow process that requires education and ample time.

Many times I reflected on the ways in which we were positioned as privileged white Americans asking invasive questions about handwashing practices, frequency of diarrhea, and death. Putting on our blue gloves to sample their drinking water felt incredibly awkward after graciously being invited inside their homes. At times, I wanted to explain that we were simply testing the water for MMM and that we would not return with any answers or solutions; that was up to MMM. Although many women we spoke with seemed excited for a solution to clean water, we couldn't promise anything. It was a humbling experience. Many of us battled with the dynamic of our obvious privilege in a village struggling to feed themselves for several consecutive months out of the year. But, it is important to remember that with privilege comes power to make change, and we can always "share the power of the microphone," as Dr. Margie Thompson says. As students and as westerners, we have powerful platforms to ensure that whatever initiatives we care most about may be heard and acted on.

If you would like to get involved in any initiatives in the WASH sector, there are many Denver-based organizations working in Sub Saharan Africa and all over the world. The Posner Center is a great resource, or visit the Water for People website.