British Museum Rejects UNESCO Recommendation to Repatriate Parthenon Sculptures

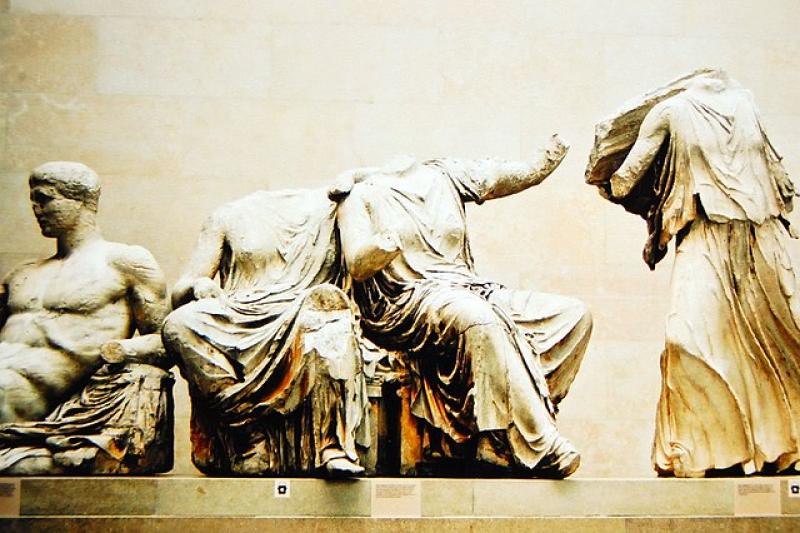

Part of the Parthenon Sculptures displayed at the British Museum. Photo courtesy of Michael Paraskevas.

In early October, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Advisory Board called on the British Museum to repatriate the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece, a recommendation flatly rejected by the museum.

The sculptures and bas-reliefs, commonly referred to as “marbles,” were originally part of the Parthenon and other temples located at the Acropolis of Athens, Greece. Created in the fifth century B.C., the sculptures adorned the interior and exterior of the temples and survived over two thousand years. By the 15th century, much of the Acropolis had fallen into disrepair under Ottoman occupation. In 1799, British ambassador Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, arrived in Athens and received permission from Ottoman officials to make casts and drawings of the Acropolis’ structures, excavate fallen pieces, and remove some pieces still attached to the buildings. According to the British Museum, Elgin took half of the surviving sculptures from the Parthenon. In the process, he inflicted structural damage and far exceeded permissions granted by Ottoman authorities. As a result, when Elgin returned to Great Britain with the marbles in 1806, he was considered “a common thief and vandal” by fellow Britons and was unable to sell the collection for ten years. Elgin finally sold the sculptures to the Crown in 1816 to pay off personal debts. By 1832, the collection was installed in the Elgin Room of the British Museum and became known as the “Elgin Marbles.”

For more than a century, the Greeks have been demanding repatriation of the sculptures as a core component of their cultural heritage. In recent years, international public pressure on the British Museum has increased substantially. According to The Art Newspaper, the gallery displaying the sculptures has been in a precarious state since World War II. In the summer of 2021, for instance, a major roof leak led to water damage in the gallery though not on the sculptures themselves.

In its recent decision, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property recommended that the British Museum return the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece. Citing poor gallery conditions, the committee sought to place additional pressure on the British Museum and the British government to begin steps toward repatriation. The museum swiftly rejected UNESCO’s recommendations, arguing that the sculptures were transported to Britain “with the full knowledge and permission of the legal authorities of the day in both Athens and London.” Museum trustees expressed willingness to lend the items to Greece with the promise of their return to London. However, they have refused offers from UNESCO for mediation, as the museum is not a government body and seeks to collaborate directly with cultural institutions.

Amid other claims for repatriation, such as those involving the Benin Bronzes, the British Museum’s struggle with Greek authorities over the Parthenon Sculptures will continue. Vigorous debate among experts, activists and the public also continues in the press and social media. In a recent Hyperallergic article, art historian Elizabeth Marlowe argued that the Parthenon Sculptures should not be repatriated at this time, before clear restitution principles are established. Readers’ comments and a follow-up statement from Dr. Marlowe indicate the intensity of these discussions, with no sign of abating.