An Essayist Explores Her Battle With Depression and Fascination With Jonestown

This article is from the fall 2021 issue of the University of Denver Magazine. Please visit the magazine website for additional content.

After 15 years teaching in the creative writing program at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, Annie Dawid (PhD ’89) left her full-time job to become a full-time writer. The poet, novelist and essayist lives in Westcliffe, Colorado, and teaches creative writing — including a course on the personal essay — for the master’s program in writing at DU’s University College.

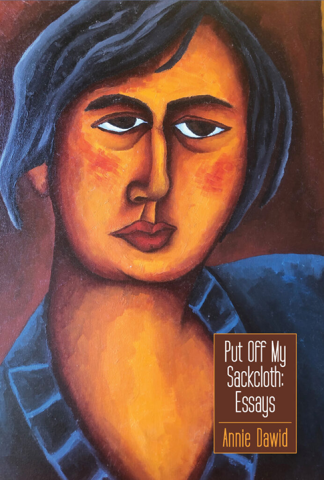

In her new collection of essays, “Put Off My Sackcloth: Essays” (The Humble Essayist Press, 2021), Dawid examines her past and explores her longstanding fascination with the 1978 mass murder/suicide at Jonestown. Her Jonestown page, posted at the Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple website, which is sponsored by San Diego State University’s Special Collections of Library and Information Access, includes many of her commentaries on the topic.

Dawid joined the University of Denver Magazine for an email discussion about her essays and the experiences and reflections that shaped them. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The pieces in this collection cover decades, from 1976 to 2020. What inspired you to weave them into a whole?

While the dates on the essays begin in the 1970s and end last year, I wrote all of them within the last 15 years, chronicling important moments in my life, hoping to cover diverse milestones. The Westcliffe pieces were local color columns I had written for the Cañon Beat, a weekly out of Cañon City, over two years. I wanted to communicate the beauty of this landscape, and some of the funny moments of a former city person grappling with life off the grid at 9,100 feet, like having to melt snow after the pipes froze and discovering that a Dutch oven heaping with snow reduces to an inch of water.

Some of your essays grapple with troubling life experiences, including your own thoughts of suicide and struggles with severe depression. How did writing about these experiences help you put off your sackcloth and deal with sorrow and despair?

The opening essay, “All Thy Waves,” which deals with a major turning point of my life, the third venture off my meds coinciding with my sole pregnancy, came about when a psychiatrist issued a call for essays written by sufferers of depression for his forthcoming book describing that condition to MDs who did not know anything about depression. I worked with him as editor before his book deal fell through. Since then, the piece won a couple of prizes for essay writing, but “Put Off My Sackcloth” is its first full-length appearance in print. I hope to transplant the reader into my skin during some of the worst moments of despair. Those who do not know depression cannot fathom how this illness can make an apparently ordinary person want to die. From reader responses, I believe the essay succeeds in that work. Medication, therapy and the love of my child moved me toward the shedding of my sackcloth. Around my 40th year, with the birth of my son, I made the switch from Depressed Person to someone who could enjoy my days, including all their vicissitudes.

Your presentation of essays is interspersed with several pieces reflecting on the 1978 mass murder/suicide at Jonestown. Why does the Jonestown tragedy loom so large in your—and the public's—imagination?

After years of research on the Jonestown tragedy — meeting survivors and immersing myself in the story of the rise and fall of Peoples Temple — I came to see that story as emblematic of the American quest for utopia, a paradigm that began prior to 1776, in which immigrants came to these shores imagining they could create a perfect society. Before I learned the story of Jonestown, I was fascinated by the communes of the 1970s and planned to write a book called “Hippie Ruins,” about two extant communes in Colorado’s Huérfano Valley. But when I was giving a reading at the University of North Dakota in 2004 and simply mentioned the word Jonestown, evoking tears in a listener who knew Jonestown survivors, I decided the story of the downfall of Jim Jones’s followers was imperative to tell immediately, and the Colorado communes could wait. The tale of followers of charismatic leaders has great relevance today. The 19 Al Qaida members who flew planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon are extreme examples of those who sacrifice rational thought to a cause and a man. The Trump phenomenon is today’s example. I became convinced that 21st century Americans need to understand Jonestown — the truths, not the myths. People born after 1978 don’t know anything about it. Or they sum up the story as “Madman Kills Zombie Followers” in a South American jungle, when the reality is so much more complicated and heartbreaking. Nine hundred twenty-four people died that day in November 1978, and the headline version is always about Jim Jones, who is not a major character in my novel, “Paradise Undone.”

The essay—“a form uniquely amenable to the processing of uncertainty”—is enjoying a revival, with younger readers awakening to its power and pleasure. What makes the essay so intriguing to read and so challenging to write?

I’ve been writing essays all my life. In creative writing programs back in the 1980s, I saw myself as a fiction writer. I didn’t want to be limited to “reality” but rather create realities in my fiction, though always based on the real world. Later, as I grew more interested in historical situations, I was drawn to stories where research was required to present verisimilitude for my characters in other eras. The essay is an exploratory, experimental form, allowing writers a freedom they may not experience in other genres. Cynthia Ozick, a great fiction writer and essayist, has shown me how it is possible to write both fiction and nonfiction in exemplary ways.