In Her New Memoir, a DU English Professor Confronts the Stigmas of Her Upbringing

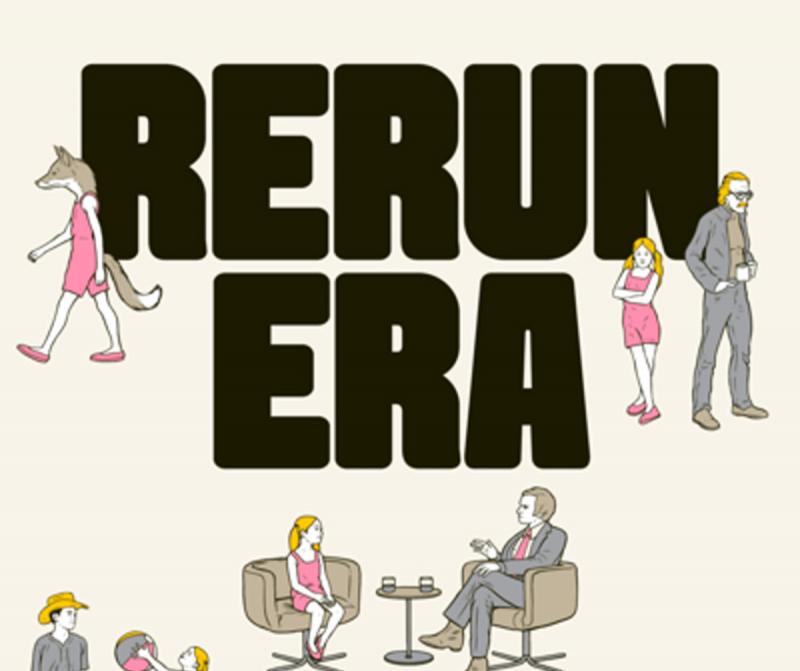

In “Rerun Era,” Joanna Howard, a professor in the University of Denver’s English department, takes readers back to a single year in her rural Oklahoma childhood, a formative few months that fractured her sense of security and forever altered her relationship with her family.

Blending adult insight with a 5-year-old’s saucy attitude, the fast-paced and humorous memoir unspools Howard’s experience of family tribulation against a backdrop of television reruns — of “Gunsmoke” and “McCloud,” “M*A*S*H” and “Taxi.” With their recurring characters and dependable air times, these provided rituals for the family and gave structure, context and color to her life. “All my adventures are there,” she writes, “inside the TV.”

Known for her lyrical prose and evocative imagery, Howard (PhD ’04) is a graduate of DU’s nationally recognized doctoral program in creative writing. For 15 years, she taught in Brown University’s creative writing program, and then returned to DU in fall 2018 with a body of well-reviewed experimental work to her credit, including “On the Winding Stair” (Boa Editions, 2009), “Foreign Correspondent” (Counterpath, 2013) and “Field Glass,” a speculative novel co-written with alumna Joanna Ruocco (Sidebrow, 2017).

“Rerun Era” is her first attempt at memoir, and it has received the same critical admiration that greeted her earlier publications. Its fans have called it “a wonderfully tactile and intimate book,” “a short, fast, laugh-out-loud read,” and “a book that you will find yourself in, lose yourself in, and long to return to again and again.”

Howard composed “Rerun Era” (McSweeney’s, 2019) in part to confront the stigma associated with her country upbringing — the father who hunted squirrels, the drawls and twangs of everyday speech, the friends and relatives who answered to monikers like Fuzz and Feral, names never accompanied by signifiers of sophistication, by professional titles or lists of advanced degrees.

“I had been urged to write this book by a colleague of mine who thought that if I would write about my family, it would make me as a writer more legible to the world,” she says. While a graduate student at DU, Howard first tried to tell her family story in novel form, but found fiction inhospitable to the effort and herself not ready for the task.

“I really needed to get to an age where I could get beyond the stigma of having grown up in what I thought of as an anti-intellectual, repressive place,” she says. What’s more, she needed to come to terms with some of the questions that face every memoirist: “Am I writing something that’s going to upset my mother? Am I writing something that is going to upset my brother; is my dad turning in his grave?”

When she finally put words on paper, she realized she was writing, in part, to reconnect with her older brother, the one surviving member of the nuclear family she was born into.

“We had this very strange upbringing where we were sort of estranged from each other because each parent sort of adopted a child and focused on that child. We just didn’t really speak until I was much older,” she recalls. “So when I was writing the book I was thinking about … pulling my brother and myself together.”

She drew on her brother’s help to reconstruct some of her memories and the loose chronology that unfolds in the book’s 164 pages. But the volume’s most astonishing accomplishment — little Joanna’s childhood, adult-informed voice — lingers long after the book’s covers are closed. “I’m pretty easily rattled,” 5-year-old Joanna relays in one of the book’s early chapters. “I get scared if anyone breathes like Darth Vader, for instance. (My brother does it. He comes into my room and breathes like Darth Vader, and I scream and run through the house.)”

Conjuring and sustaining that voice required intense concentration. “If I’m known in fiction for anything,” Howard explains, “it’s this kind of lyric style. It’s very important to me that no matter what I’m doing, even if I’m doing a kind of clean, transparent prose, it has to have turns of phrase that seem unusual or unique. That’s like my standard. That’s my hallmark. And so I had to figure out ways to give the voice this strangeness that would make it sound probably other than a 5-year-old.”

Beyond exploring her childhood memories, Howard also aimed to revisit a discarded place, an environmentally distressed part of the country whose people have been elbowed out of the national conversation. In a chapter on the so-called “rural purge” of the late 1960s and early 1970s, for example, she puzzles over the mass cancellations of popular television shows with small-town themes and characters: “The Andy Griffith Show,” “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “HeeHaw,” all replaced by sitcoms with urban settings and preoccupations.

"So all of it just stopped,” she writes in a chapter titled “Dislocation/Relocation.” “One day, we turn on the TV and no more Marshall Dillon and Chester/Festus, no more hay rides, no more kissing cousins and DaisyDukes … and no more houses on the prairies or the banks of plum creek or anywhere rural. Just gone, like that.”

Also gone: the political culture that once characterized eastern Oklahoma. There and then, deep in the Bible Belt and well before the culture wars accelerated, her independent mother could read Ms. magazine and her truck-driving father could spout off about his Union politics without anyone raising a judgmental eyebrow.

Now that her memoir is in readers’ hands, Howard looks back at the writing process with wonder. It was feat enough to survive the “Rerun Era” first time around; it was something else entirely to revisit it for publication.

“I wrote it in like two weeks,” she says of the book. “I didn’t sleep. It was really manic. … But once I started, I felt like I wouldn’t be able to survive the book if I didn’t just get it out.”