The Reality of History

This article is from the fall 2021 issue of the University of Denver Magazine. Please visit the magazine website for additional content.

Lisa Rubiner.

Gloria Emerson picks up the phone. She wants to make sure I have the right number.

Once, in New Mexico, she tells me, a woman sat in the front row of a lecture she delivered, wide-eyed and grinning ear-to-ear. “I’ve always wanted to meet you,” she said as Emerson exited the stage. “Will you please sign my book?”

No, she is not that Gloria Emerson—the hard-nosed New York Times writer who famously spurned the fashion beat for on-the-ground war reporting from Vietnam. She never confronted John Lennon and Yoko Ono on the effectiveness of their peace activism.

But this Gloria Emerson—the 83-year-old University of Denver alumna (BA ’62)—has produced some deep, confrontational work of her own.

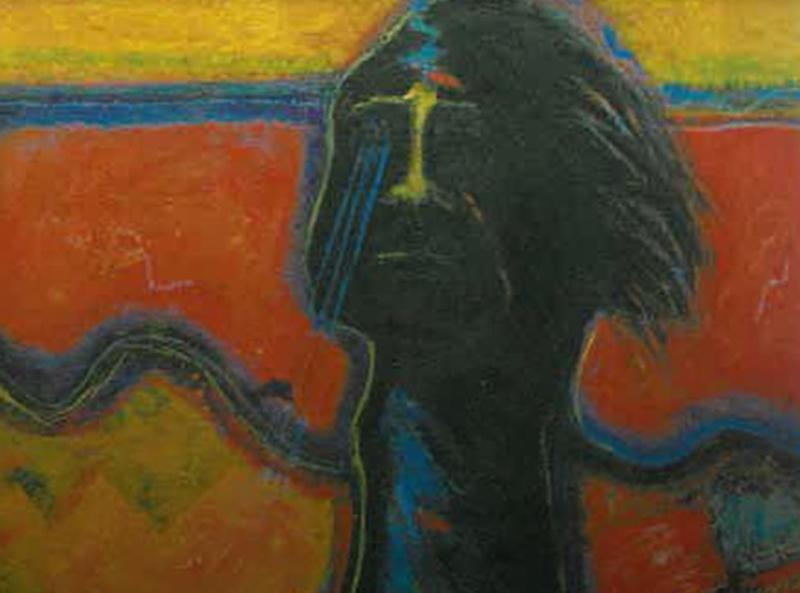

A set of 11 water-based acrylic paintings serves as a visual interpretation of the Sand Creek Massacre—her reaction to a 1981 book of provocative poetry, titled “from Sand Creek,” by Acoma Pueblo writer Simon J. Ortiz.

“The issues we have to deal with are brutal,” says Emerson, who is a member of the Navajo Nation. “Some of my people write poetry of beautiful landscapes, beautiful us. And we are, but we also have the history.”

That history is also part of Colorado’s history. On Nov. 29, 1864, on the banks of Sand Creek in the southeastern part of the state, U.S. volunteer troops charged a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho Natives, who had been promised protection by the federal government. At least 230 Native people—most of them women, children and elders—lost their lives in the bloodshed, even after Chief Black Kettle raised a white flag in surrender. The perpetrators burned the settlement and mutilated the dead before departing.

Roughly 150 years later, a University of Denver committee concluded that the neglect, poor leadership and reckless decision-making of territorial Gov. John Evans, who co-founded Colorado Seminary, as DU was then known, in 1864, created the conditions that enabled the violence. Col. John Chivington, who planned and carried out the massacre, was a founding board member of Colorado Seminary.

Depicting such a horrific event was anything but easy, Emerson says, and not just because of what happened that day.

Often, she wondered what a Navajo woman was doing interpreting an Acoma Pueblo man’s poetic interpretation of a massacre that devastated bands of Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho people. Her sister’s cancer diagnosis and subsequent death only made facing the subject even more difficult.

Ultimately, the artist filled each canvas with bright and colorful figures and symbols. Her imagery partially obscures Ortiz’s poetry. Selective words peek out from behind the paint.

News that DU is planning a memorial dedicated to the Sand Creek Massacre got her thinking about the tragedy again. The University intends for the memorial to honor the lives and communities lost and damaged in the brutal attack and its aftermath, while also serving as a place for learning and healing.

Art provides a powerful way of contending with the loss, as Emerson has learned. She hesitates to classify herself as a lifelong or naturally talented artist. Although she drew and wrote poetry as a young girl on a New Mexico reservation, she never felt called to pursue the arts as a career.

Instead, she attended DU in hopes of becoming a social worker. After graduation, she worked for the state of New Mexico and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Emerson thrived as she worked in her home community, buoyed by the 1960s wave of progressive social change. Not long after, she attended Harvard, earning a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Education.

But at age 50, the arts came calling.

“A lot of my work [to this point] was social service oriented,” Emerson says. “I felt I was giving out [a lot] and not doing anything for myself. I don’t know why I was compelled to go to the Institute of American Indian Arts, but that seemed to be my salvation. It was a way to finally acknowledge that talent.”

In a classroom of 19-year-olds, Emerson began to find her artistic voice. “I had been smothering the creative part of me by doing what I thought I was supposed to do,” she says.

Emerson’s Sand Creek paintings came to life later, during a three-month stay at the School of American Research in Santa Fe. With studio space and materials provided, she created the poetry and paintings that appear in her 2003 book, “At the Hems of the Lowest Clouds: Meditations on Navajo Landscape.”

She sold a couple of canvases, destroyed a couple of others. The work that survived now sits, unglorified, in a back storage room at her home near Shiprock, New Mexico. They’re not the sort of paintings, she says, that anyone wants to buy and hang in their living room. Her family, in fact, considers the work to be “grotesque.”

Does that bother Emerson—that those closest to her dismiss some of her most impactful work?

“Nope,” she says, flatly. “Navajo women don’t go around dealing with death and brutality like I did.”

She didn’t necessarily want to break the stereotype, she explains. But she felt so moved by Ortiz’s Sand Creek poetry, she almost had to.

“Sand Creek is not my history,” she says. “It’s the history of other tribes. But in general, I think we have to acknowledge the reality of our history.”