A 2016 Election Postmortem

This article originally appeared in the fall issue of University of Denver Magazine.

“Stunning” is the word Seth Masket uses to describe Nov. 8, 2016.

As he watched news reports announce Donald Trump as the United States’ 45th president, Masket, a professor of political science at the University of Denver, reacted not only as a voter, but as a scientist, carefully considering a surprising result.

“After a lot of years of observing elections, that was something I didn’t think was a likely outcome,” he says. “Like everyone else, I’d been following the polls. … We had been spending months asking people for whom they were going to vote, and most of them said Hillary Clinton. I didn’t think that kind of an outcome could happen and yet it had. On a very professional level it was really disorienting.”

Even before any votes were cast on that November Tuesday, Masket, who directs DU’s Center on American Politics, had been mulling an idea for a new book. Predicting a Republican loss, he planned to follow the party’s efforts to rebuild. When it became clear that wouldn’t be the case, he instead looked to the fascinating challenge ahead of Democrats in the wake of a complicated defeat.

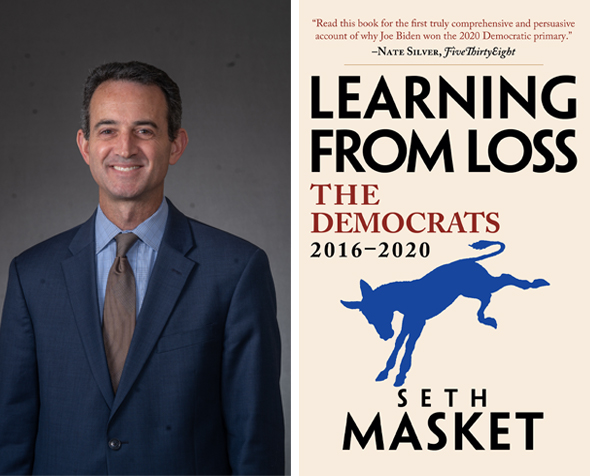

In September 2020, after four years embedded among the Democratic party’s top activists, leaders, office holders and interest groups, Masket released his findings in his book, “Learning From Loss” (Cambridge University Press, 2020), which details the Democratic Party’s decision-making process in the wake of the 2016 election all the way through to 2020’s primaries and caucuses.

Political researchers and journalists are often quick with detailed dissections of party decisions, but Masket says they often miss the behind-the-scenes conversations, thinking and strategizing. He aims to illuminate these in “Learning From Loss.”

“There’s a big black box there about the conversation a party has before it makes a decision,” he says. “I wanted to catch a party in the act of processing an election loss and trying to come to terms with it and figuring out why [they lost]. What is it that cost them an election that they probably could’ve won if they’d done something different? Then what do they do with that information?”

After interviewing 65 people (some on a regular basis), spending a summer in Washington, D.C., and making annual trips to each of the country’s early caucus states, Masket began to understand the answer to one important question: Why did Hillary Clinton lose? Or rather, why do people think she lost?

“I’m not that interested in what the truth is,” he says. “I am more interested in what party actors believe was the truth and what they do with that.”

Although party activists speculated widely on the source of Clinton’s defeat — that she was a poor candidate, that she was a woman, that Trump is a talented politician, that the campaign ads were all wrong — about a third of Masket’s interviewees had a different explanation: identity politics.

“This is the idea that Hillary Clinton spent a lot of time championing underrepresented groups — women, people of color, the LGBT community, young voters and others — without ever reaching out to working-class whites,” Masket explains. “As a result, they felt excluded from the Democratic message, and they responded by switching over to the Republican side.”

The evidence doesn’t support this explanation, Masket notes, but as a narrative, many found it persuasive. So much so that, out of the Democratic party’s largest and most diverse candidate pool ever, Joe Biden became the party’s nominee.

Many voters were surprised by this outcome, but Masket wasn’t. As early as fall 2019, he saw the writing on the wall.

“[Biden] wasn’t the best debater or the best public speaker or the most successful fundraiser. He didn’t have the most enthusiastic base or anything else. He was picked. This wasn’t a contest so much as the party making a decision,” he says. “They decided they wanted Biden because they were prioritizing electability above other things. They thought a moderate white guy would be more electable against Trump than someone else might be. And a lot of people in the party were willing to give up a lot of things they cared about for what they saw as a more likely win.”

With the 2020 race still, as of press time, in full swing, it’s too soon to know if the Democrats’ strategy paid off. But Masket’s study is sure to offer valuable insight for whichever political party emerges the victor or the loser. Masket, meanwhile, will finally learn the end of the story he’s spent four years telling — the culmination of work he calls “the most rewarding research of my life.”