COVID-19 and the History of Disease in Early America

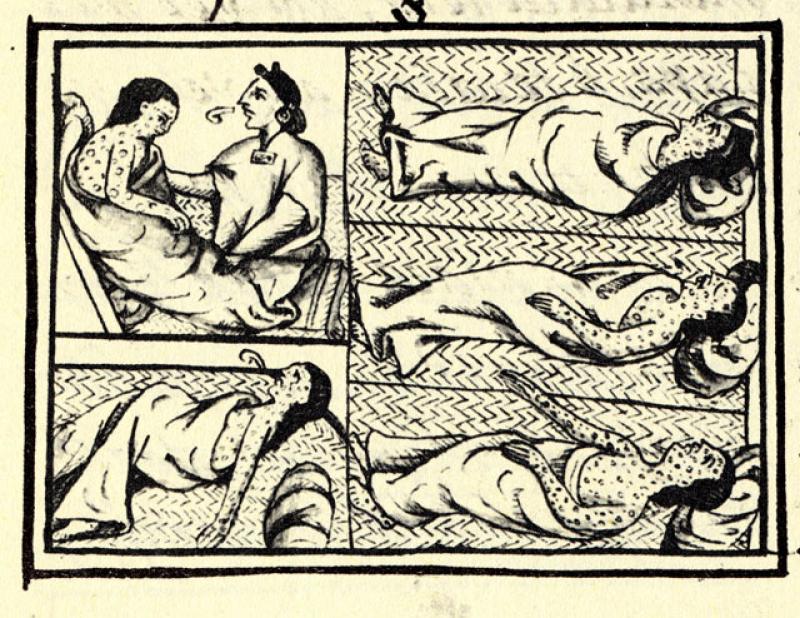

Panel from the Florentine Cortex depicting smallpox outbreaks in the Americas during the 16th century

“What social anxieties does COVID-19 lay bare for us to see? What ought to be done about them?” These are the questions David Korostyshevsky, adjunct faculty in the Department of History at the University of Denver, asks in his Disease in Early America course.

Korostyshevsky uses historical epidemics, such as smallpox and cholera, as case studies to explore how human beings experience and respond to disease. During COVID-19, specifically, this course has been a way to connect past to present, allowing students to see their current world in new ways.

Beginning with encounters between Native American and European populations, students first examine smallpox as a powerful biological and social force. Korostyshevsky wants students to see connections between the changing relationship between science and religion, concepts of disease and the development of public health institutions.

These changes are what captured Sara Gorski’s attention. Gorski, a first year studying environmental science, is fascinated by changes in medical understanding of disease over time.

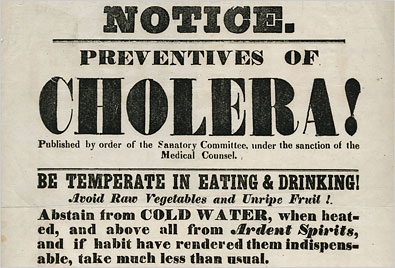

“The class started with smallpox in the 16th/17th centuries where medical understanding of disease was almost nonexistent. As we changed gears to the cholera outbreaks in the 1800s, it was very interesting to see the change in medical knowledge.”

Bailey Kord, a senior majoring in English & literary arts, also noted evolutions in public health systems that radically changed the spread of disease in America.

“We spent a lot of time studying cholera outbreaks, which had a huge effect on the concept of sanitation. Sewer systems were being built in order to combat disease, some of which are still in use today.”

Viktoria Trbovich, a senior majoring in psychology with a minor in history, pointed out that “pigs used to roam the streets of New York like rats and mice scavenging for food, and they were the only ones cleaning the streets of our cities.”

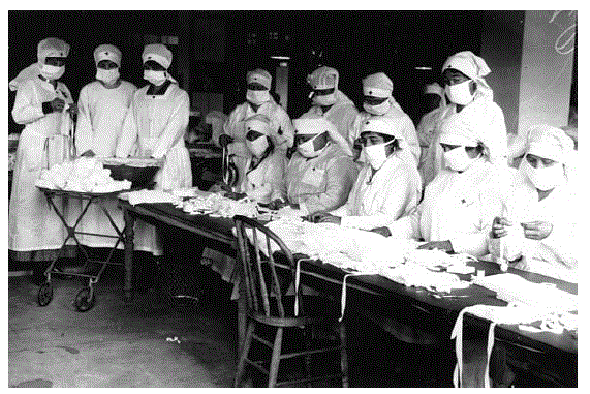

In a time of online teaching, Korostyshevsky has brought historical events and circumstances to life through a variety of primary source documents, group discussions, Zoom-based classes, reflective essays and critical perspectives from historians and guest speakers. Pulitzer Prize-winning CU-Boulder historian, Elizabeth Fenn, spoke with students about her work on early American smallpox epidemics as biological warfare against Native American people.

"Fenn's talk illuminated the significance of early American smallpox outbreaks as well as drew important connections to today's events," Korostyshevsky said.

Despite advancements in medical understanding and treatment of disease today, students in Korostyshevsky’s course were struck by persistent similarities between past events and present circumstances. Meghan Garrant, a senior double majoring in criminology and German, noted the abundance of connections that can be drawn across time and place.

“People’s reactions to the pandemic show me that we really haven’t learned from our past. People do not believe scientists and experts about the spread of COVID-19, just as citizens did not believe John Snow and emerging germ theory back in the 19th century.”

Garrant and her classmates emphasized common social issues that persist today and the ways in which disease, socioeconomic status and other social issues — such as race and gender — intersect.

“In early American history, the wealthy bourgeois would literally escape to the countryside where they had access to clean running water, while the urban poor could not escape. We are seeing that now where impoverished people in America still have to work to live despite the risk of the pandemic, while wealthier families can afford to stay home.”

Trbovich added, “We also see people responding with a fear that causes hatred. In the past, people were shunned, rejected and even murdered because they were thought to be the problem in society that caused and/or maintained this great sickness.”

Reading about and discussing current social issues has increased awareness regarding contemporary experiences of, and responses to, COVID-19. Issues of conquest and military invasion, enslavement, urban poverty, immigration, gender disparity, public health policy, conflicting government response, misinformation and more connect to broader questions of what health and disease mean and how shifts in meaning expose existing social problems.

“I urge students, who are citizens and future professionals,” Korostyshevsky explained, “to see these parallels between the past and present as a call to action to make our world a healthier and more equitable place for all people.”

Korostyshevsky’s students have taken this to heart, noting their increased awareness of disease as a social issue and their strengthened understanding of disease response from multiple (and often conflicting) public figures.

“Beliefs, arguments and discussions that people are having now also played out back then,” explained Kord. “It's kind of unbelievable how similar the discussions in 2020 America are to those from 1832. Despite how different things are now, we are still following the same patterns of the past.”

Trbovich hopes history will not continue to repeat itself in these ways.

“In the past, our nation has not seen any real change in fighting diseases until everyone was willing to fight it together as a collective, not focusing on the self, our individual wants and desires, but wanting to better our present and future by working on the health of our nation today and being willing to sacrifice for the right to a better future.”

“I hope we can all learn to lay down our privilege to better the lives of others and the health of this nation on the intersecting levels of physical, economic and political health, which have been afflicted each in different ways.”