DU Research Highlights How Therapy May Reduce Depression During Pregnancy

For those who may experience depression during pregnancy, finding the right treatment or support can be a challenge. A team of researchers from the Stress Early Experience & Development (SEED) Research Center at the University of Denver are trying to change that.

Approximately 17% of pregnant individuals meet criteria for a major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis and up to 37% report elevated symptoms during pregnancy, according to research on the topic.

But viable solutions may be out there.

In fact, early findings published in JAMA Psychiatry show that a safe, prenatal intervention — in this case MOMCare and brief interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) — can result in rapid decreases in depression among pregnant individuals from diverse racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

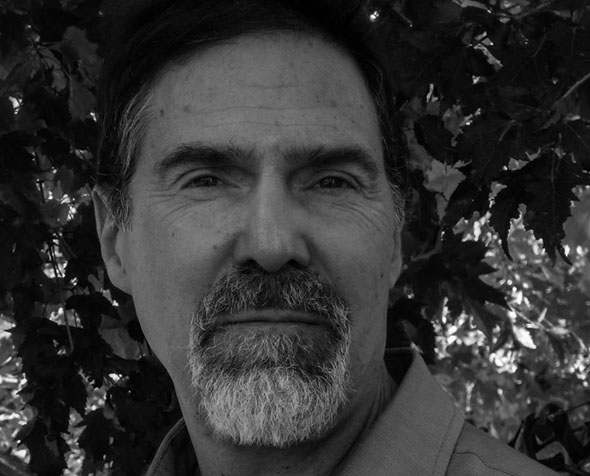

The results from this initial study are very encouraging, according to DU Department of Psychology Professor Elysia Poggi Davis. It’s also a topic Davis has long been interested in — specifically how mental health and stress in pregnancy can impact not only the pregnant person but also the developing fetus.

“There are profound changes in the prenatal period; it’s often a time associated with a number of different mental adjustments and it’s a time — from a prevention, intervention standpoint — when people have more interactions with the health care system than they might in other phases, and so there are opportunities to provide support,” she said.

Davis served as the co-primary investigator along with Benjamin Hankin, associate head and director of clinical training and the Fred and Ruby Kanfer Endowed Professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Co-authors from DU also included postdoctoral fellow Catherine Demers, Assistant Visiting Clinical Professor Sarah Perzow and Ella-Marie Hennessey, second-year clinical psychology graduate student.

Mary Curran, clinical supervisor/therapist at the University of Washington, Robert Gallop, mathematics professor at West Chester University and Camille Hoffman, associate professor of Maternal Fetal Medicine in the University of Colorado Departments of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Psychiatry, were also co-authors.

Participants were recruited from two health clinics in the Denver metro area between July 2017 and August 2021, resulting in 234 total pregnant individuals whose screenings showed elevated depression symptoms.

Those who participated were randomly selected to receive either an engagement session and eight active sessions of brief IPT or enhanced usual care (EUC), which included engagement and maternity support services. Of 234 participants, 115 were allocated to IPT and 119 received EUC.

Depression was assessed at the beginning and throughout pregnancy. Depression diagnosis in the “intervention group” dropped from 37% before intervention to 6% after — compared to 26% in the control group. Further, individuals in the intervention group self-reported lower depression symptoms quickly after the start of treatment.

Reducing depression in pregnancy is likely important for both the mother and the developing fetus. Davis and colleagues will continue to follow up with the children whose parents participated in the study. They are working with Psychology Assistant Professor Jena Doom to assess child health outcomes at three to five years old.

And these results are just the beginning for the Care Project team.

Davis and DU Psychology Professor Galena Rhoades are taking this research one step further, in partnership with Denver Health Medical Center, by recruiting 900 pregnant individuals over the next five years to receive either in-person or virtual group counseling.

Anyone who is pregnant, a Denver Health patient, and speaks Spanish or English is eligible to enroll.

“Not only is this group intervention more efficient and potentially more cost effective, but I also think there’s going to be some advantages from meeting other people and making those kinds of connections,” Davis said.

Once the prenatal counseling sessions are complete, the research team will follow both mother and child through infancy and childhood to assess outcomes.

“We’ve just started, but we’ve even gotten some anecdotal feedback about people making connections with other members of the group and this feeling of you’re not the only one who’s experiencing stress during pregnancy,” she said.