FanExpo Panel to Address Holocaust Education Through Comic Books

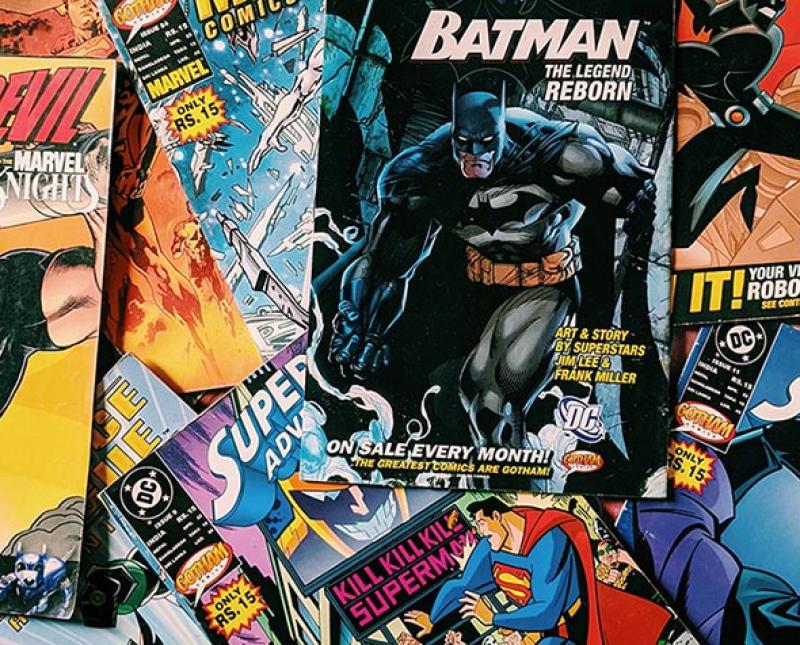

With vivid colors and bombastic villains, quips and unsuspecting heroes, comic books have captured the hearts of millions — imaginary worlds with real-world impact.

On Friday, July 1, the Center for Judaic Studies (CJS), which resides at the University of Denver’s College of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences, hosted a panel at FanExpo Denver called “The Holocaust in Comic Books: Preparing for Colorado Bill HB20-1336.”

In a first-of-its-kind Holocaust education panel, the event discussed how the Holocaust appears in comics, the importance of Holocaust education and resources for the new state teaching standards, including the CJS’ website survivalandwitness.org. FanExpo Denver is a major annual convention for sci-fi, horror, anime and gaming fans, similar to Comic Con.

Selena Naumoff, executive assistant for CJS, spearheaded the panel project, combining her two passions: Holocaust education and comic books.

As she ruminated on the idea of hosting a panel at FanExpo Denver, she happened to be speaking with Helen Starr, a second-generation Holocaust survivor. That’s when Starr mentioned her friend Erin Christian, a Denver-area teacher who uses comic books to teach about the Holocaust.

“What did you just say to me?” Naumoff said. “This is what I want to do.”

Christian, a proponent of HB20-1336, has been incorporating graphic novels into her middle school curriculum since 2014, including Maus, a graphic novel stricken from eighth grade curriculum in Tennessee.

"One of my students said, 'if children had to live through this, we can read about it,'" Christian said. “When they can visually engage with something, it makes it more real for them. We focus on the visual analysis, why the artists and writers would construct the panels in certain ways and the leading techniques to emphasize certain moments.”

HB20-1336, which goes into effect July 1, 2023, requires Colorado public schools to incorporate Holocaust and genocide studies into current coursework required for graduation, a culmination of years of advocacy work by the Starr family.

**

Aug. 11, 2017.

As dusk turned to night, a group of white supremacists descended upon Charlottesville, Virginia. Young men in khakis and dark colored shirts donned swastikas around their arms.

Helen and her mother Fanny Starr, a Holocaust survivor, watched from their home in Denver.

“Are you seeing this? Can you believe it?” Helen asked her mom.

Armed with torches, the menacing group circled around the Robert E. Lee statue to protest its removal.

“Blood and soil,” they shouted. “Jews will not replace us.”

For Fanny, the grisly scene felt familiar. It reminded her of Kristallnacht, also known as the Night of Broken Glass, in 1938, where Nazis torched synagogues and vandalized Jewish homes, business and schools, ultimately killing nearly 100 people.

Glued to the television, they couldn’t look away.

“Why, why, why are we the victims?” Fanny said.

Haunted by the following day’s deadly white supremacist rally, the Starrs reached out to an evangelical church. Their request was clear: renounce this abomination from the pulpit.

The church refused, and instead of extinguishing the flames of hatred and bigotry, it fanned them.

**

Still, the Starrs pressed on, advocating for Holocaust education, which eventually led to the passing of Colorado HB20-1336. In October 2020, months after the bill was signed by Gov. Jared Polis, Fanny passed away.

Since then, Helen has made it her mission to keep her mother’s legacy alive. Helen has spoken at a variety of Holocaust education events, but the FanExpo panel will be different. It’s a chance to reach a new audience — comic book lovers, young and old.

Like most art, comic books often underscore social and political commentary.

“A lot of people don’t realize it necessarily, but a lot of comics fold in the Holocaust,” Naumoff said.

In 1940, the creators of Superman, Jewish writer Jerry Siegel and Jewish artist Joe Shuster, theorized how Superman would end World War II. Busting through the ceiling of Hitler’s retreat, Superman would grab Hitler by the throat.

“I’d like to land a strictly non-Aryan sock on your jaw. But there’s no time for that! You’re coming with me while I visit a certain pal of yours,” said Superman, referring to Joseph Stalin in the comic “How Superman Would End the War.”

In March 1941, nearly a year before the U.S. entered World War II, Captain America made his debut, delivering a right hook to Hitler’s jaw. Armed with a red, white and blue shield, Captain America was designed to be a patriotic superhero.

“It was when a group of people didn’t know what was going on in the war. What better way to use a superhero figure?” Helen said.

In the decades after the war, many more comics weaved the Holocaust and the Third Reich into their storylines, educating about Nazi genocide as a way to never forget.

“It’s easy to forget key parts of history. As the years pass, the key events fade, and it can feel like a mystified story rather than a factual time in history,” Helen said, quoting her mother. “We can read books, see movies and view pictures, but can we ever truly grasp the reality of the Holocaust?”