Religious Studies Adjunct Professor Connects Past to Present with Cross-Disciplinary Work

"How do people answer the question, why am I here and what is my place in the world? How do people identify what is 'true' or 'best'? What are the psychological and social effects of a person's beliefs and practices?"

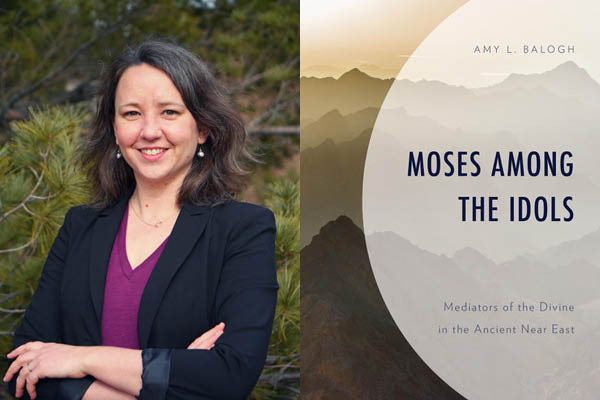

These are some of the primary questions that drive Dr. Amy Balogh, an adjunct professor in DU's Department of Religious Studies and program manager at the Center for Judaic Studies.

Growing up in a churchgoing, mid-Western household, Balogh has long been interested in "what humans are doing when they 'do' religion." As an undergraduate, Balogh realized she could turn this interest into an academic career, pursuing a degree in biblical studies. Since then, she's gone on to specialize in ancient Semitic languages, Near Eastern religions, and Near Eastern archaeology through her master's and doctoral programs.

"There is always something new to discover about the ancient world and its inhabitants," says Balogh. Religious studies offer insights into the people of antiquity. What fascinates Balogh is how this historical view can illuminate "modern issues and the trajectory of our species in meaningful ways."

In the classroom, Balogh emphasizes a longue durée or "long duration" approach, which focuses on aspects of history that develop slowly. Rather than viewing events as discrete moments in time, her courses, like Creation & Humanity, The Emergence of Monotheism, and The Moses Traditions, unpack religion as a slowly changing phenomenon anchored in an ancient past.

As a result, she helps students understand that "religion is more complex than most people realize; even its revolutionary moments are surrounded by a long history in either direction."

Balogh's cross-disciplinary interests bring this approach to life. She focuses on ancient textual study and the interpretation of archaeological finds, adopting anthropological and comparative methods into her contemporary research praxis.

Her book Moses among the Idols: Mediators of the Divine in the Ancient Near East (Lexington/Fortress, 2018), was nominated this year for an American Academy of Religion Best First Book in the History of Religions Award. In this text, Balogh explores the biblical figure of Moses whose closest analogue in the ancient Near East is that of the idol. Using Moses as a book-long case study, Balogh illustrates the fruitful work of cross-cultural comparison.

As she explains, "The book brings religious, biblical, and Near Eastern studies into dialogue over a long-standing issue. Though past offenses in the use of one another's material have caused many in these disciplines to abandon cross-cultural comparison, Moses among the Idols argues for ethically-conscious comparison by addressing the issue of method itself."

When she isn't in the classroom or lecturing on her work at community churches and synagogues, Balogh is working on a project (and second book manuscript) entitled Human Ecology in Ancient Near Eastern Religions: A New Theory of Origins.

This project counters the idea that ancient religions grew out of fear and ignorance of nature and instead suggests such belief systems are the outcome of an ever-present tension derived from humankind's experiential relationship to the natural world.

In an age when issues of climate change urge a new orientation toward nature, Balogh's work uses eco-psychological and comparative methods to rethink how we arrived at our modern-day crossroads in the human-nature relationship. Drawing on case studies from Israel, Jordan, Egypt, and Turkey, she explores environmental zones, landscapes, and archaeological sites that hold the ancient stories of our human ecology.

Balogh captures the importance of her cross-disciplinary approach in a metaphor: "Human existence is a spider web—everything is hitched together with precision so that changes in any given thread or node have repercussions for the entire structure. The study of human existence ought to be just as intricate and interconnected."

As learners, teachers, scholars—as people—"we owe it to ourselves to engage such interconnections," says Balogh "because they tell us not only where we have been, but where we are going."