Q&A: Race & Immigration in the U.S.

Ahead of her Livingston Live Webinar on October 22, Elizabeth Escobedo, associate professor of history, answered some questions on the history of immigration and race in the U.S. Escobedo specializes in 20th century Mexican-American history and is the director of diversity, equity and inclusion for CAHSS. She oversees the Casa de Paz Learning Community and the Critical Race & Ethnic Studies minor program.

In your upcoming Livingston Lecture, you’re going to discuss the role of race in the history of immigration in the US. Can you provide one example that illustrates this relationship?

It is not surprising that the majority of immigrants in detention today are people of color, given the historically intertwined relationship between race and immigration policy in the United States. For instance, the first federal laws regulating immigration to the United States specifically targeted Chinese immigrants, reflecting the racism and nativism of the era. Anti-Chinese sentiment, based on fears over job competition and beliefs that the Chinese belonged to a lesser race and were unfit to ever become “true” Americans, led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The act suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States for 10 years and reaffirmed existing laws that banned Chinese aliens from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. (The exclusion laws were renewed in 1892 and not repealed until 1943.) Chinese laborers could thus no longer immigrate lawfully to the United States, and if they did so in violation of the law, the law’s provisions made them deportable. (This was also the first deportation provision passed by the federal government.) In specifically excluding Chinese laborers because of their race and class, the law set the stage for twentieth century U.S. immigration policy, which is marked by its racial and class biases. And as a number of U.S. immigration historians note, the 1882 act marks the transformation of the United States from a so-called nation of immigrants into a country defined more by its gatekeeping.

What recent policy changes have directly impacted US immigrants?

Perhaps one of the more marked recent policy changes is the way in which the Trump administration is utilizing the pandemic to suspend asylum for individuals claiming persecution and looking for refuge in the United States. A recent public health order from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention closed the border to migrants without valid travel documents, including families and unaccompanied children, noting Covid concerns. But these attempts to end asylum protections for migrants on the southern border are not new; the administration has worked for years to close the border to those with legitimate claims to asylum. So we now have a situation where humanitarian laws are being completely ignored, and migrants are unable to make their case to asylum officers or in U.S. immigration court; rather, they are being systematically deported back to dangerous situations in their home countries, most in Central America.

The situation is particularly dire for unaccompanied minors looking to claim asylum. Since the spring thousands of migrant youths have been sent back to their home countries, rather than being allowed to make an immigration claim and taken into the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, where they would typically be transferred to a sponsor in the United States, usually a parent or family member. Most recently, we’ve seen news stories of migrant children that are traveling alone and apprehended, then held secretly in hotels by private contractors before being sent back to their home countries. This is just another example of the ways in which the U.S. federal government is hindering asylum claims and fostering family separation at the border — plain and simple.

How did you become involved with the Aurora immigrant-advocacy group Casa de Paz?

Casa de Paz first came on my radar after I read a 2016 Westword piece about Sarah Jackson, executive director of Casa, and her efforts to support immigrants recently released from the GEO detention center in Aurora. I was so inspired by her vision and efforts and was in the midst of preparing to offer a twentieth century immigration course for the Department of History in the coming academic year. Given the vitriolic anti-immigrant rhetoric on the local and national stage, I had been trying to figure out a way to include a service-learning component for students to work one-on-one with migrants in order to foster empathy and better understanding of the human side of immigration debates and policies. I contacted Sarah and subsequently learned that Katie Dingeman-Cerda, at the time a postdoctoral teaching fellow in sociology, had worked with Casa in a summer immigration class, and Sarah was eager and ready to continue the DU relationship. My Immigration in the Twentieth Century U.S. course ran in fall 2017, and it quickly became clear that students were hungry for this type of experiential course work, and in making connections between course materials and their volunteer experiences supporting migrants. It was also clear that Sarah Jackson greatly appreciated DU students becoming a part of the Casa volunteer team. That’s where the idea for the Casa de Paz Learning Community was born: Rather than simply offering one Casa service-learning history course every other year or so, we now offer multiple Casa service-learning courses each year, from a number of academic disciplines, including anthropology, history, sociology and Spanish. Through these courses, students receive hands-on volunteer experiences, including visiting migrants at the detention center; serving as hosts or companions to help migrants reconnect with family members upon their release; providing hospitality to migrants at the Casa by cooking meals, cleaning and collecting and organizing donations; and Spanish translation and interpretation for Spanish-speaking migrants. Additionally, students have an opportunity to take a number of similarly themed courses, and to understand the complexity of an issue such as immigration from a variety of disciplines.

In what ways have students been impacted by their participation in the Casa de Paz Learning Community?

We’ve had overwhelming success in seeing students positively impacted by their participation in the Casa de Paz Learning Community. For instance, instructors in the learning community often hear that their experience at Casa was “life changing” for their students. As one student in Professor Sergio Macias’ winter 2020 SPAN 2350: Latin American Culture & Society course stated, the course fundamentally changed their views of the world in regard to family separation and “an unfair system based on racial prejudice and ignorance.” Another student in this class reflected that “the service learning has been a pivotal aspect of the class that has taught me a lot about empathy and the immigration system in the U.S. I will continue volunteering with Casa de Paz once the quarter is over.”

These types of sentiments are not unusual. The volunteer experience affords students the opportunity to engage with communities that are different from their own, not only for their own benefit but also for the benefit of community members. By participating in these unique learning experiences, then, students are getting a more holistic perspective beyond what they are reading or discussing in class. As one of Professor Lisa Martinez’s students shared in a class assignment, it is one thing to read about the plight of migrants in detention, but it is quite another to hear it from a person experiencing it in real time. Along similar lines, another of Professor Martinez’s students noted how much they had in common with the person they visited with at the GEO Detention Center in terms of age, taste in music and favorite past times, something they did not expect to be the case before they volunteered. Thus, above and beyond course readings and assignments, these types of interactions speak to the importance of experiential education, particularly given the demographic composition of DU students.

Where should people go to learn more about your work?

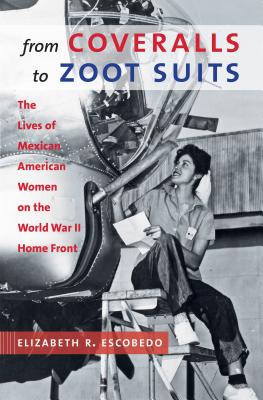

Much of my research focuses on the experiences of second-generation women of immigrant populations during times of war. In particular, I’ve written about American-born women of the Mexican community and the ways in which World War II represented an unprecedented historical moment that provided second-generation daughters with new means to exercise control over their lives in the home, workplace and nation, despite continued workplace inequities and family and communal resistance to their broadening public presence. You can learn more about these extraordinary women in my book, “From Coveralls to Zoot Suits: The Lives of Mexican American Women on the World War II Home Front” (University of North Carolina Press, 2013). My current book project continues to explore my interests in the interactions of gender and race in the wartime context, with specific attention to the histories of Mexican American and Puerto Rican women in the U.S. Armed Forces in World War II, and as veterans in the postwar era.

Register here for the Livingston Live Webinar with Elizabeth Escobedo on October 22.