Q&A: The COVID-19 Crisis in Guatemala

In celebration of Latinx Heritage Month, September 15 through October 15, DU's College of Arts Humanities & Social Sciences reached out to Associate Professor of Anthropology Alejandro Cerón to learn more about his involvement with the pandemic response in Guatemala.

Can you tell us a little about your primary area of research?

My long-term research looks at the relationship between public health and the idea of health as a human right. I start by asking what meanings people and institutions give to “public health” and the “right to health.” In this context, I have done research projects mostly in Guatemala that deal with access to health care, discrimination in health care facilities, access to medicines, chronic kidney disease, pandemic preparedness and more.

In the context of the pandemic, my colleagues in Guatemala and I have tried to be helpful and respond to the emergency. Information is a key resource and reliable knowledge about the disease is crucial to many people, communities and organizations. I’ve seen how some of the same issues related to public health institutions and communities are at play during the pandemic.

Can you provide some context on how the COVID-19 crisis has evolved in Guatemala?

Although the Guatemalan government’s response to COVID-19 was mostly well-received when it announced the first confirmed case on March 13, it was clear by the end of April that information had not been transparent, and containment and mitigation measures were not being implemented with clear criteria or protocols. Aside from the loud political opponents and COVID-19 deniers active on social media, the majority of people seemed to be trying to do their part in controlling the pandemic. As the rate of new confirmed cases and deaths started to increase during the second half of May, and with confirmed cases in most of the country’s 340 municipalities, community leaders and organizations started to ask for operational guidelines they could follow.

How did you become involved in distributing these guidelines for Guatemala’s COVID-19 response?

In April 2020, Lesly Ramirez contacted me in her capacity as coordinator of Pacto Ciudadano’s Health Commission to ask if I could help her team in putting together community guidelines in response to COVID-19. Pacto Ciudadano is an alliance of 14 coalitions that brings together more than 100 organizations in Guatemala that seek to create technical and public policy proposals that contribute to the much-needed reform of the State and a model of inclusive development for the country.

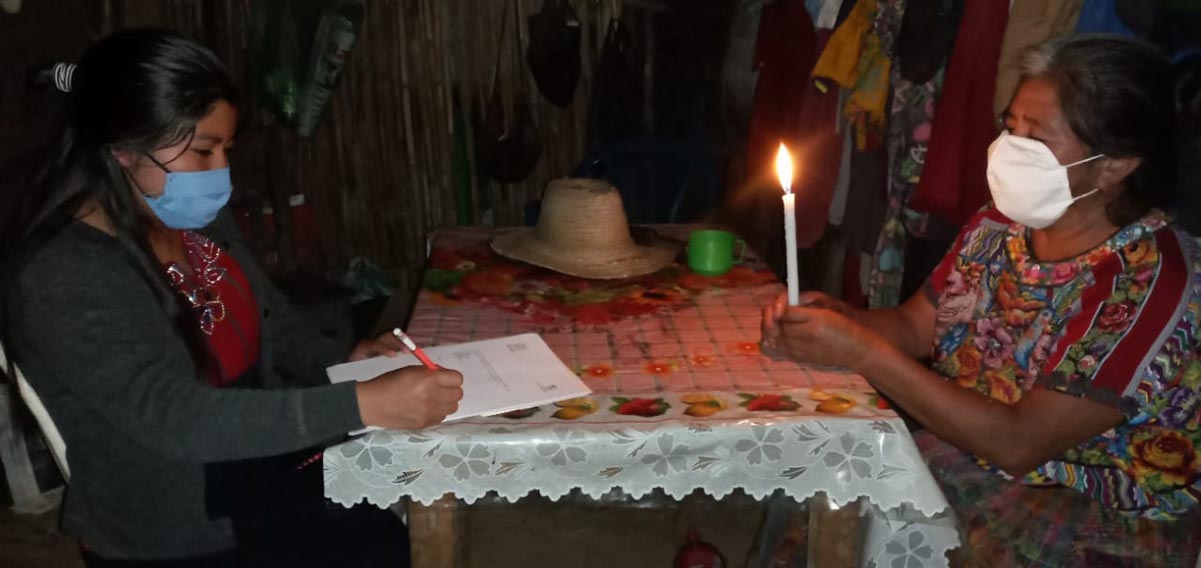

Some community leaders needed advice on how to request or reject sanitary cordons, as well as all sorts of minutiae about isolation, quarantine and caring for sick people in specific situations. As one community organization’s leader put it, “We just want scientific information to get ready for when the virus comes.” This is how Lesly Ramírez and Aída Barrera, a physician with masters’ degrees in nutrition and epidemiology, began the task of putting together the community guidelines and eventually reached out to me to support them in this task.

What kind of challenges have you faced in tailoring a response for many different communities that are facing the pandemic?

Defining the target audience, level of education, primary language (there are at least 23 indigenous languages spoken in Guatemala) and rural/urban emphasis have been huge challenges. We have opted for targeting people with the equivalent of a high-school education and Spanish proficiency, with the assumption that they will then adapt messages as they see fit. We have also started to produce short videos with subtitles in Spanish and audio in the most widely spoken indigenous languages, starting with K’ichee’. We have three other videos in different languages in production.

The subjective experience of the pandemic has also been hard to deal with. I feel that between May and June we were all focusing on prevention and mitigation, but starting in July the focus shifted at least in part to treatment and the shortcomings of the government’s response. This reveals the importance of influencing on the policy level, so some of the Health Commission’s efforts have also shifted in that direction.

How were students and DU’s Ethnography Lab involved with this project?

Zoi Johns, who double majors in international studies and anthropology, was the undergraduate research assistant for DU’s Ethnography Lab during this project. She worked with me in designing and putting together the website. She is a remarkable student, highly motivated and organized, always happy to apply her skills in the “real world.” It was helpful that she has a very good command of Spanish and general web-design interest.

This past August, the DU Ethnography Lab has started to build a partnership with a network of organizations in Colorado who are looking into how COVID-19 is affecting farmworkers and other food industry workers. Their work involves supporting workers as they face the pandemic, as well as influencing policy to address the vulnerabilities they systematically are subjected to. The Ethnography Lab will support this effort’s data gathering, analysis and dissemination, while offering DU students opportunities to develop their skills and knowledge in meaningful ways.

Learn more about ways to get involved with DU's Ethnography Lab by visiting their resources page.